General Microbiology

GENERAL

Bacteria are unicellular microorganisms having a variety of characteristics allowing their classification. One major classification scheme is based upon their staining properties using the "Gram stain" procedure. In this procedure, heat-killed bacteria are exposed to the purple dye crystal violet and iodine. This combination forms a dye complex in the bacterial cell wall. Treatment of the stained bacteria with a decolorizer like ethanol will wash away the dye complex from some bacteria but not others. Bacteria that retain the crystal violet-iodine complex appear purple and are called "Gram-positive". Bacteria that lose the dye complex can be counterstained with the red dye saffranin so that they appear red. These bacteria are called "Gram-negative". The basis of the Gram reaction lies within the structure of the cell wall, described below.

Bacteria also come in many different shapes. Spherical shapes are referred to as "cocci" while elongated cylinders are called "bacilli" or "rods". Some bacteria are slightly elongated cocci and these are referred to as "coccobacilli". Even other bacteria have a corkscrew-like appearance; these spiral forms are often called "spirochetes". Individual cells may also be arranged in pairs or clusters or chains. Thus, may morphologies are possible and these can be useful for the identification of bacterial genera. (Click here to see a bacterial classification flowchart).

The ability of a bacterium to cause disease is known as its virulence. Factors involved in determining virulence potential are discussed here. In terms of the medical aspects of bacterial structure, we are most interested in those features that interact with the host. These features are found predominantly on the outer surface of the bacterial cell. This page will describe some of these features.

SURFACE APPENDAGES

Bacteria may or may not possess surface appendages that provide the organism with the ability to be motile or to transfer genetic material or to attach to host tissues. These appendages are outlined below:

Flagella: These are the organs of motility. Flagella are composed of flagellins (proteins) that make up the long filament. This filament is connected to a hook and rings that anchor the flagella in the cell wall. In Gram-positive bacteria, there are two rings attached to the cytoplasmic membrane; in Gram-negative cells, an additional two rings are found in the outer membrane. Flagella may be up to 20 μm in length. Some bacteria possess a single polar flagellum (monotrichous), others have several polar flagella (lophotrichous), others have several flagella at each end of the cell (amphitrichous), and still others have many flagella covering the entire cell surface (peritrichious). Counterclockwise rotation of the flagella produces motility in a forward motion; clockwise rotation produces a tumbling motion. Flagella may serve as antigenic determinants (e.g. the H antigens of Gram-negative enteric bacteria).

Pili: These surface appendages come in two distinct forms having distinct purposes. Pili (or fimbrae) include:

Sex pili: This form of pilus can be relatively long but is often found in few numbers, generally 1 to 6, protruding from the cell surface. These structures are involved in conjugation, the transfer of genetic information from one cell to another. These structures can also provide the receptor for certain male-specific bacteriophages.

Common pili: This form of pilus is usually relatively short and many (about 200) and can be found covering the cell surface. These structures provide the means for attachment to host cells (e.g. epithelial cells) and often play an important role in colonization (e.g. N. gonorrhoeae).

SURFACE LAYERS

Bacteria possess several distinct surface layers that can enhance their pathogenicity. These layers are outlined below:

Capsules: This type of surface layer is composed primary of high molecular weight polysaccharides. If the layer is strongly adhered to the cell wall, it is called a capsule; if not, it is called a slime layer. These layers provide resistance to phagocytosis and serve as antigenic determinants. The production of capsules is genetically and phenotypically controlled.

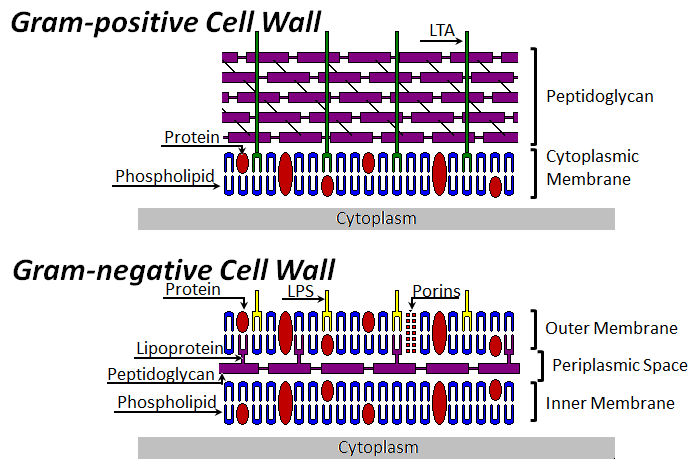

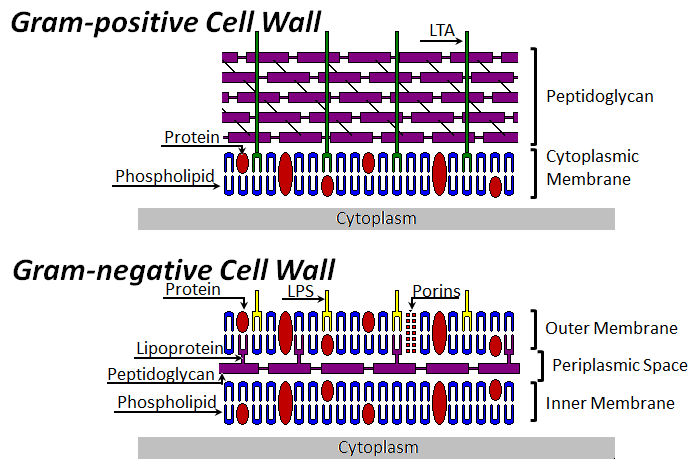

Cell wall: The cell wall is the basis for classification of bacteria according to the Gram stain. Gram-positive bacteria have a thick layer of peptidoglycan external to the cytoplasmic membrane. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a thin layer of peptidoglycan located between the cytoplasmic membrane and a second membrane called the outer membrane. This region is known as the periplasmic space. Other important constituents of the cell wall include the following:

Peptidoglycan: This is a polymer of alternating N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) and N-acetylglucosamine (NAG). Long strands of this alternating polymer may be linked by L-alanine, D-glutamic acid, L-lysine, D-alanine tetrapeptides to NAM (Click here to see a graphic representation). Gram-positive cells have a much more highly cross-linked peptidoglycan structure than Gram-negative cells. Peptidoglycan is also the "target" of antimicrobial activity. For example, penicillins interfere with the enzymes involved in biosynthesis of peptidoglycan while lysozyme physically cleaves the NAM-NAG bond.

Lipoteichoic acids: Lipoteichoic acids (LTA) are found only in Gram-positive bacteria. These polysaccharides extend though the entire peptidoglycan layer and appear on the cell surface. As a consequence, these structures can serve as antigenic determinants.

Lipopolysaccharides: Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are found only in Gram-negative bacteria. These structures are composed of lipid A, which binds the LPS in the outer membrane and is itself the endotoxic portion of the molecule. The polysaccharide moiety appears on the cell surface, serving as an antigenic determinant ("O antigen").

ENDOSPORE FORMATION

In order to transmit disease, pathogenic bacteria must have a means of surviving transit from one host to another. Many organisms rely on human-to-human contact while others can survive in the environment some short periods of time. The extreme ability to survive environmental conditions is observed in organisms capable of forming endospores. Two important pathogenic genera that are capable of this transformation are Bacillus and Clostridium. The process of sporulation begins when vegetative (or actively growing) cells exhaust their source of nutrients and involves seven distinct stages of differentiation. In the spore form, the organisms are very resistant to heat, radiation and drying and can remain dormant for hundreds of years. Once conditions are again favorable for growth, the spores can germinate and return to the vegetative state.