Helicobacter pylori ulcer diagram

Helicobacter pylori ulcer diagramGNU Free Documentation License

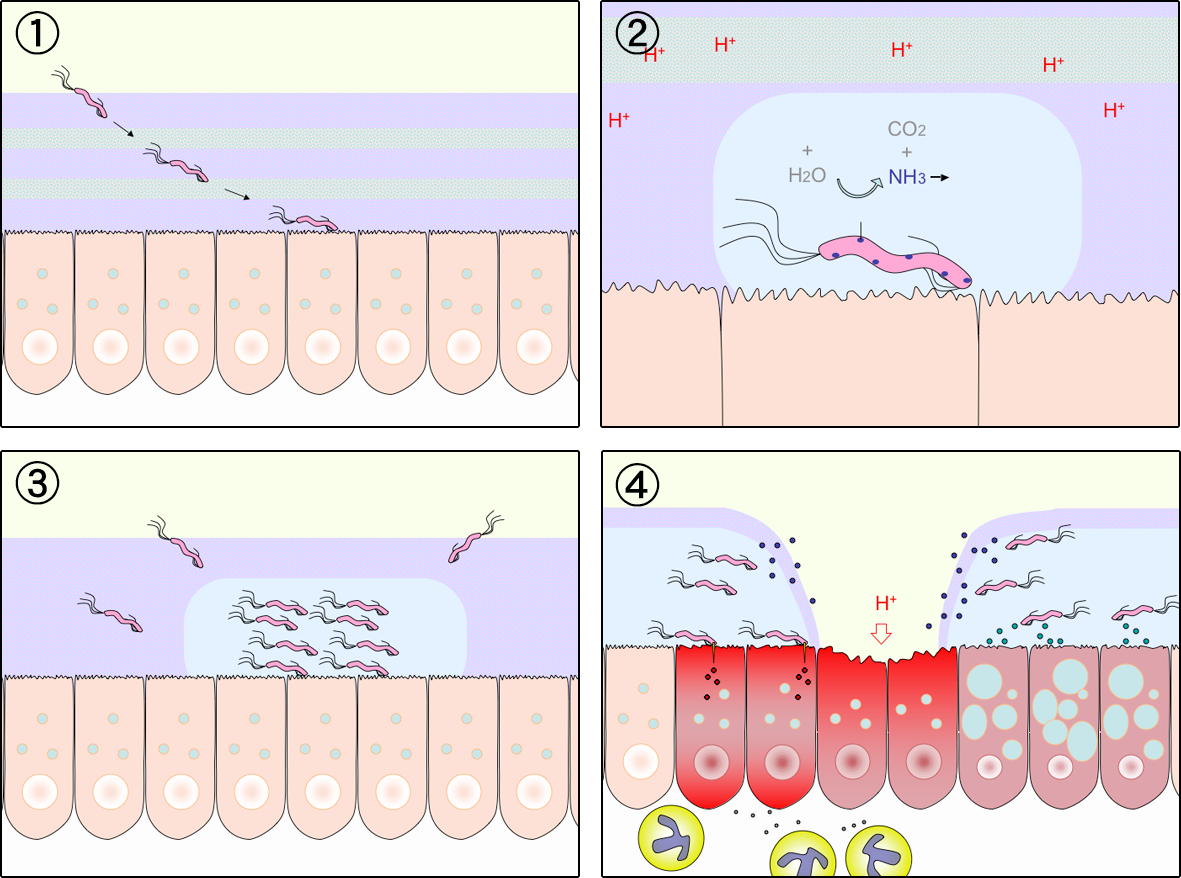

- The specific mode of transmission and mechanism of H. pylori is unknown, however, direct person-to-person transmission is suspected.

- H. pylori may be spread either by the fecal-oral or oral-oral route. The organism has been cultured from the stools of infected children, and from dental plaque, and its DNA has been detected in saliva using Polymerase Chain Reaction.

- Essentially, all persons infected with H. pylori develop chronic superficial gastritis involving the antrum and the fundus of the stomach. Infected persons may develop peptic ulcer disease, lymphoproliferative disease, chronic atrophic gastritis and gastric adenocarcinoma years to decades after initial infection.

- H. pylori infection is associated with chronic gastric inflammation. Inflammatory effector molecules released by the organisms induce tissue inflammation and release of nutrients. This process of inflammation may serve as a means for the organism to obtain constant nutrients.

- H. pylori infection results in the down regulation of somatosatin-producing D cells, which in turn leads to elevated gastrin levels and enhanced gastrin acid secretion and eventually ulceration at the site.

- A carrier of H. pylori usually has no symptoms, but persons with gastritis or ulcers may have the following symptoms: abdominal pain, dyspepsia or indigestion, bloating and fullness, mild nausea, belching and regurgitation, weight loss and hunger every 1-3 hours.

- Research has indicated that H. pylori infection may lead to gastric cancer via a series of events: chronic superficial gastritis → atrophic gastritis → atrophy → incomplete intestinal metaplasia → dysplasia and finally adenocarcinoma.