enemy action

or from the normal hazards of being at sea, a numbing 9 percent

loss rate. If you went to sea in a Liberty ship - especially from 1942

to mid-1943 - your odds of completing

more than one voyage were not that great.

enemy action

or from the normal hazards of being at sea, a numbing 9 percent

loss rate. If you went to sea in a Liberty ship - especially from 1942

to mid-1943 - your odds of completing

more than one voyage were not that great.

Liberty Ship Model

The S.S. John Randolph was

one of 2,710 Liberty ships completed during the frenzied U.S. shipbuilding

program of World War II. Of those, 253 were lost - sunk by enemy action

or from the normal hazards of being at sea, a numbing 9 percent

loss rate. If you went to sea in a Liberty ship - especially from 1942

to mid-1943 - your odds of completing

more than one voyage were not that great.

enemy action

or from the normal hazards of being at sea, a numbing 9 percent

loss rate. If you went to sea in a Liberty ship - especially from 1942

to mid-1943 - your odds of completing

more than one voyage were not that great.

She was a standard EC2-S-C1 cargo

vessel, laid down on July 15, 1941, at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards

in Baltimore, Md., and launched with little fanfare on Dec. 30, when Hull

No. 0019 slid down the ways and was formally christened the S.S. John

Randolph (a noted Congressman and Senator from Virginia). Things happened

quickly after that. Completed on Feb. 27, 1942, by May she was in eastbound

Convoy PQ-16 as one of the first Liberty ships to make the dreaded and

hellish convoy run to Murmansk, Russia, as the United States strove to

shore up its understrength ally. From May 24-30, 1942, German aircraft

made 245 bomb and torpedo attacks against PQ-16, sinking eight and damaging

four out of 36 merchant ships (1).

The John Randolph was lucky, weathering the hurricane of steel the

Nazis threw at her (that I was able

to discover).

christened the S.S. John

Randolph (a noted Congressman and Senator from Virginia). Things happened

quickly after that. Completed on Feb. 27, 1942, by May she was in eastbound

Convoy PQ-16 as one of the first Liberty ships to make the dreaded and

hellish convoy run to Murmansk, Russia, as the United States strove to

shore up its understrength ally. From May 24-30, 1942, German aircraft

made 245 bomb and torpedo attacks against PQ-16, sinking eight and damaging

four out of 36 merchant ships (1).

The John Randolph was lucky, weathering the hurricane of steel the

Nazis threw at her (that I was able

to discover).

Her luck ran out on the trip back. On July 5, 1942, while transiting the Denmark Strait near Iceland, westbound Convoy QP-13 was groping through thick fog when it ran into a newly laid and inaccurately charted Allied minefield. The John Randolph was one of four ships lost; five men died either in the initial explosions or the scramble to abandon ship (2). She lived less than five months, but in that time the John Randolph did her duty, ferrying vital supplies for the war effort as part of the greatest industrial build up the world has ever seen.

I singled out the John Randolph

because she seemed like a representative and nominally historic Liberty ship; it would

also give me an opportunity develop new skills by showing a heavily-weathered and

well-used vessel with the decks covered with all manner of cargo, plowing

through the stormy North Atlantic.

The plastic kit (No. SW2500) is Skywave's 1/700 scale Liberty ship; actually it's a navalized version of a Liberty ship, hence the AK-99 moniker on the boxtop. The U.S. Navy needed lots of cargo ships, and being the Navy, they added stuff - two more 20-mm gun positions on the midships superstructure, which was also enlarged aft; more substantial masts for all the signal flags the Navy likes to use; a searchlight platform on the funnel; and an additional armored crows nets on the No. 3 kingpost. Some of these were easy enough to scrape or chisel off; some I missed (the extra 20-mm positions); and some were due to (again!) inadequate research, in this case the cutout in the bulwarks at the aft deckhouse. That did not become a standard feature of Liberty ships until mid-1943.

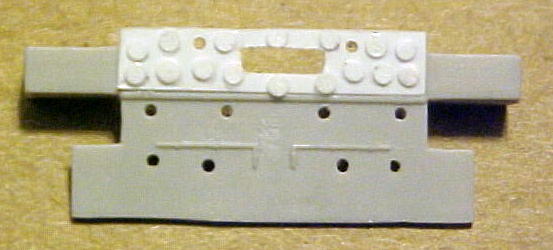

With the usual ton of reference photos in hand (but as noted above, not thorough enough research), I set to work. The model itself goes together fairly quickly, but as usual I took the roundabout way, getting very small-detail oriented. The scuppers along the sides of the hull had to be bored out with a No. 75 drill. As did the portholes, and new portholes had to be added in the correct places.

Then there was the weird armor plating.

Liberty ships were built fast and cheap; steel was not something

to be wasted. Swiping an idea from the ever-inventive British, the U.S.

added extra armor around the bridge/radio room and gun tubs with the same

stuff they surface roads with - asphalt. Mixed with granite chips. And

held in place with metal bands and metal fasteners. It looked very

weird, but it was better than plain quarter-inch steel. Here are a few construction shots:

|

|

|

| All of the scuppers along the edge of the main deck had to be bored/reamed out with a small drill bit. The moldings in the kit are quite good. | Portholes had to be added along the sides of the main deck level of the superstructure, and on the front as well. And yes, they are crooked - you should always either pencil a line or use tape to make sure the holes line up! | |

|

|

|

| Front of the superstructure shows where I drilled and filed out the bridge window opening, replacing it with a very special piece of clear plastic, and added a thin piece of sheet styrene and small styrene disks made with my Waldron punch to simulate the added asphalt armor. | Side of the superstructure, showing the area where armor was added. The penciled oval is where a door goes, but I forgot that paint was going to cover that up. These styrene disks are too big, but were as small as my Waldron miniature punch-and-die set could produce. (I now have the sub-miniature set as well). | |

|

|

|

| Adding thin plastic strip around the various gun tubs, to simulate the bands that held on the asphalt 'armor plate' on Liberty ships. | A bonus shot, my snazzy and well-equipped, highly organized work bench (insert laugh), showing the major subsections before painting and final assembly started. |

As you can see, a lot of drill work was required so holes looked like holes instead of recesses in lumps of plastic. It takes time and a steady hand, but the end results are worth it. In a scale this small, you can't do much with the details, so it's the little things that can add up into an interesting model.

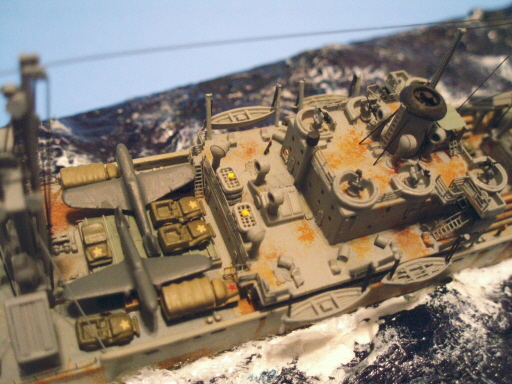

I wasn't able to find out what the John Randolph carried as deck cargo on that first Murmansk run (didn't want to spend months waiting for the National Archives to ferret it out) so I improvised - and threw in a little of everything! Boats, all kinds of vehicles, sewer pipe, aircraft ... one thing about the Liberty ships, anything and everything was piled on top as deck cargo once the holds were full. I found photos of Liberty's carrying locomotives, landing craft, semi-trucks, an entire tugboat (seriously) and anything else you could think of.

I also used some different colors for this model - the more I looked at it, the more I felt that the Flat Gull Gray (Testors Model Master 1930) I'd used on the two Victory ship models was too light. I wanted something a little darker, but not so dark that it robbed the model of all visible details. I settled on Navy Aggressor Gray (Model Master 1994) and this time did the hull, decks and superstructure all the same color.

To break things up color-wise, the P-40s were

painted in dark gray Schwarzgrau RLM 66 (Model Master 2079) to simulate the protective

coating that airplanes riding as deck cargo sometimes

got. Other small deck and ship

equipment items were painted Dark Gull Gray (Model Master 1740) to make

them stand out a little. The Lend-Lease 'Russian' GMC trucks were painted Afrika

Corps khaki (Model Master 2098) to set them apart from the other vehicles;

they also got red star decals. The halftracks, jeeps and weapons carriers were

painted several shades of olive drab. The motor launches did end up in

Flat Gull Gray (gotta' maintain some consistency). Hatch covers

were again painted RAF Interior Green (Model Master 2062), but a couple

of them were darkened with brown paint to indicate 'newer' canvas;

all were then Weathering the ship to make it look rusty and abused was done mostly

with drybrushing - dabbing just the end of the brush in the paint, wiping most

of that off on a paper towel, and then either 'stabbing' the brush at the deck

or scrubbing it to put down a mottled, uneven, but very light coat of

paint. You

have to be careful, go slow and use a light touch, or you end up with dark blobs

of paint that look like ... dark blobs of paint, instead of the rust

effect you'd

hoped for. (PRACTICE this on some

scrap plastic before trying it on a model. Trust me on that one).

I did not use my Rustall

weathering set because quite honestly, I've never been able to get a really

thick coat of rust on something with it. The colors I used were Testors rust (1185),

flat brown (1166) and orange (1127) and Model Master Rust (1785). Of those, the

flat brown looked the weathered with a light wash of acrylic black paint to simulate

wear and tear. I was pleased with how that effect turned out.

weathered with a light wash of acrylic black paint to simulate

wear and tear. I was pleased with how that effect turned out.

most like rust when it

was drybrushed on the decks or streaked down from the scuppers along the sides

of the hull. Using the different shades and sometimes overlapping them helped

give the uneven appearance of real rust. The orange was used in only a few

spots, very tiny dots to represent fresh rust, which once dry was then drybrushed over

with one of the brown shades to tone it down. Little

pools of 'spilled oil' were added in several deck areas with the aforementioned

thinned black acrylic paint.

most like rust when it

was drybrushed on the decks or streaked down from the scuppers along the sides

of the hull. Using the different shades and sometimes overlapping them helped

give the uneven appearance of real rust. The orange was used in only a few

spots, very tiny dots to represent fresh rust, which once dry was then drybrushed over

with one of the brown shades to tone it down. Little

pools of 'spilled oil' were added in several deck areas with the aforementioned

thinned black acrylic paint.

It took several evenings before I was satisfied, but I think the end result looks good, especially at normal viewing distance. After I 'rusted' the decks, I masked off several areas and painted them with a different shade of gray to make it look like the deck crew was at least trying to stay ahead of the problem; Dad told me that unless they were in port, the crew never went over the side to paint the hull, it just got rustier and rustier until the ship went into drydock (which was once a year if the ship was very lucky).

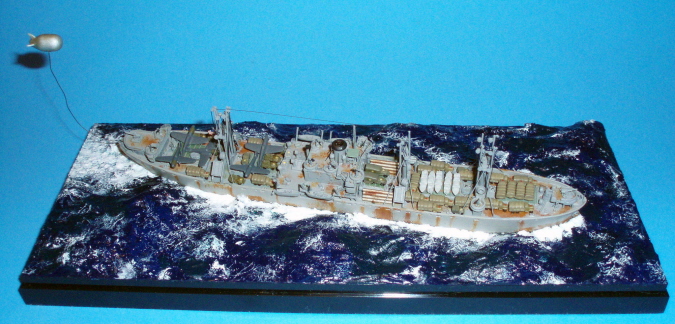

The other major challenge for this model was water - for the

first time, I was going to try and put a waterline model on an 'ocean' base ...

and naturally I wanted to make it harder by trying to model the big waves of the stormy North

Atlantic. There are tons of how-to's about this on

the Web, so I read up and then went to the local arts and crafts store and

bought:

Since the display case base was black, I scrounged some

black styrene sheet for testing various 'ocean' color combinations. The experts

at this said the Atlantic is bluer than the Pacific, and the North

Atlantic would have a gray tinge to it, especially in the winter/spring. I finally

settled on 3 parts blue, 1 part green and 20 or so drops of dark gray acrylic

paint for each batch. I masked off the edges of the base, sanded it roughly

to give it

some 'tooth' and then put down a couple of coats of my ocean color with a wide

flat brush.

When the paint was thoroughly dry, I started on the waves.

First I cut a

template of the bottom of the hull out of some thick plastic stock, so I could

sculpt the waves around that shape without having to worry about getting acrylic gel on the model. Then I laid down several thick, parallel lines of gel at an angle

to the base (it looks weird if everything is perfectly squared up), let them

dry thoroughly, then added more gel, gradually building up each line

of 'waves' until

they looked about right. This

is all very subjective, but it's my model, so I get to decide what looks

'right'. The gel is water soluble,

so I applied it and shaped each wave with a wet, broad-bristled disposable

brush, trying to get the uneven look of the ocean. The

gel dries to a milky/clear finish; you can kind of see where more needs to

go. When each application started to get tacky dry, I 'stippled' the surface by

jabbing it lightly with the stiff-bristled disposable brush held perpendicular to the gel,

giving it an

uneven finish (big waves aren't smooth). When doing this, you have to

remember that the wake from the stern of the ship will be almost flat for a

distance behind it. Looking at color photos of ships under way in various kinds

of seas helped me get a picture in my mind of what it should look like when

done.

After the waves were where I wanted then, I got a

broad, smooth brush, mixed more of the ocean color and carefully painted the

surface. Move the brush slowly to avoid bubbles in the finish. I also

mixed some slightly lighter and darker shades of the 'water' color and applied

them in irregular patches so the surface wouldn't look so monochromatic.

In some respects I simplified the rigging of this

model by putting all of the cargo booms in the stowed position (at the tops of

the kingposts instead of horizontal to the deck) because all of the

hatches were going to be covered with

While they

were drying, I made the 'cables' by stretching out lengths of sprue over

a candle until I got

very thin diameters. These were colored with a permanent black Sharpie marker and

allowed to dry. I also painted lengths of .025 styrene rod my chosen gray,

measured how long the booms needed to be (the two on No. 2 kingpost are a little

shorter) and glued them in position so I could measure how much

space there was between the end of each kingpost and the tip of each cargo boom.

Be sure to use your dividers or calipers! This gave me how long each 'run' of block-cables-block had to be.

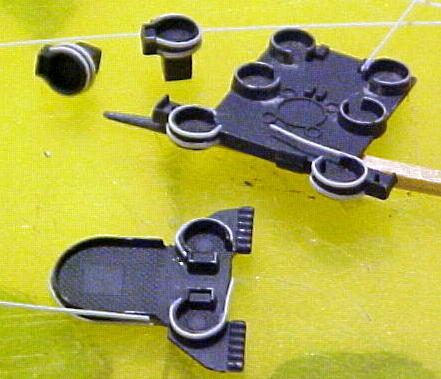

When

everything was dry, I lined up 6 pulley halves on a piece of tape, cut off the

required lengths of blackened sprue and attached them with super glue. Each

block requires two lengths of sprue parallel to each other. Before the glue

dried I made sure the sprue 'cables' were parallel and then tapped another

pulley half lightly down on top. After that side was dry, two more block halves

were added to the other side to make a complete assembly. Ten sets were

needed for the cargo booms. I prefer stretched sprue for rigging because 1)

It's free, 2) I can get relatively thin diameters that look to scale, and 3)

It's stiff, so there's less worry about it sagging after installation. I also

used stretched sprue for the radio aerials.

When the model was

almost done I decided to add a barrage balloon to the mix. Some were included

with the Skywave Beachhead Vehicles set, I found pictures of Murmansk

convoys using them, so I figured what the heck. The only question was, How

were they rigged?

Research revealed that, you guessed it, no one

was really sure. A Liberty ship volunteer in San Francisco said it looked like a cable was run from one of

the winches at No. 5 hatch to a pulley on the No. 3 kingpost and then to a

bracket on the top of the mast ... which wasn't going to work for me because

the display case I bought only had a couple of inches of clearance at the top.

So

I compromised and added a hawser reel to the stern, aft of the 5-inch gun

platform. A length of 30-gauge wire proved sturdy enough to hold the plastic

barrage balloon, so a small hole was drilled in the deck at the base of the

hawser reel to insert one end of the wire into. The balloon was painted

with aluminum (Testors 1181) to mimic the aluminum-doped fabric of the

real balloons. A coat of semi-gloss over the aluminum toned it down and evened

it out. Although not 'scale' as far as the length of the cable

goes (2 inches [117 feet] instead of 17 inches [1,000 feet]), it still looks pretty cool with the clear

plastic display case top in place.

Other little insane detailing bits

included:

Scratchbuilding

the lifeboat davits out of plastic rod, and then gluing the lifeboats on so

they hung at the correct angle to reflect the ship's roll to

starboard (lifeboats were

always kept swung out in combat areas, for a quicker escape); Drilling out the spaces

between the webbing in the bottoms of the six rectangular rafts on the aft

superstructure; Adding four crew figures. In

weather as bad as what I depict, nobody wanted to be out on deck any longer

than necessary (Can you find all of them in the photos?); Drilling out the waste

discharge ports on the port side at the waterline; Adding some soot stains to

the top of the superstructure mast, to reflect the coal-fired propulsion of

Liberty ships Adding a rim around the

anchor hawse holes with 30-gauge wire formed around the correct sized

drill bit. Is this an exact replica of the John Randolph on

that first Murmansk run? Of course not. I missed some details (filling in the

aft bulwark cutouts, for instance) and some things I had no way of finding out,

like what her deck cargo load was for that trip.

When all is said

and done, however, I believe this model is a faithful representation of a

Liberty ship doing what it was designed to do - haul the 'bullets, beans and

bandages' that our fighting men needed across the oceans of the world. Here are

a few more shots of the finished model, showing some more of the detail work

(and I apologize in advance for the slow loading time):

The picture of

the rust on the port bow also shows the one major structural modification I made. I wanted my ship to be listing (leaning) wayyyy over to one side,

after recalling Dad's vivid stories of 40 and even 50 degree (or even more!) rolls while

on Victory ships, which were a lot more stable than the Liberty's. I took

a strip of 0.125-inch thick styrene and glued it along half of the hull

lengthwise after roughly shaping it, then smoothed out the joint with Tamiya

putty and sanding

sticks and painted the new plastic red (Floquil Boxcar Red 110074) to represent the

below the waterline hull. When all was done, it gave the model a pronounced list

to the right.

The picture of

the rust on the port bow also shows the one major structural modification I made. I wanted my ship to be listing (leaning) wayyyy over to one side,

after recalling Dad's vivid stories of 40 and even 50 degree (or even more!) rolls while

on Victory ships, which were a lot more stable than the Liberty's. I took

a strip of 0.125-inch thick styrene and glued it along half of the hull

lengthwise after roughly shaping it, then smoothed out the joint with Tamiya

putty and sanding

sticks and painted the new plastic red (Floquil Boxcar Red 110074) to represent the

below the waterline hull. When all was done, it gave the model a pronounced list

to the right.

Very small amounts of the titanium white were drybrushed along the tops of some

of the waves, or in the valleys between them to represent breakers and streaks of foam. The

wake along the sides and aft of the ship was mostly titanium white, heavily stippled and with a few splotches of very

light blue or blue-green, with more white drybrushed over the top. I did not, as

some suggest, coat the entire surface with Future floor wax to give it a

glistening shine - to me it looked fine as it was, with Future drybrushed over random

patches. As you can

see from the picture, it turned out OK - for a first effort!

Very small amounts of the titanium white were drybrushed along the tops of some

of the waves, or in the valleys between them to represent breakers and streaks of foam. The

wake along the sides and aft of the ship was mostly titanium white, heavily stippled and with a few splotches of very

light blue or blue-green, with more white drybrushed over the top. I did not, as

some suggest, coat the entire surface with Future floor wax to give it a

glistening shine - to me it looked fine as it was, with Future drybrushed over random

patches. As you can

see from the picture, it turned out OK - for a first effort!

cargo. After

experimenting

with my Waldron miniature and sub-miniature punch and die sets, I found a

diameter that seemed to look the best for all the pulleys (blocks in sailor

talk) I needed to make. After punching out a bunch from .005 sheet styrene, I

stuck them to a piece of blue painter's tape, painted them gray, let them dry,

flipped them over and painted the other side.

cargo. After

experimenting

with my Waldron miniature and sub-miniature punch and die sets, I found a

diameter that seemed to look the best for all the pulleys (blocks in sailor

talk) I needed to make. After punching out a bunch from .005 sheet styrene, I

stuck them to a piece of blue painter's tape, painted them gray, let them dry,

flipped them over and painted the other side.

Cutting the wheels off

the four trucks on No. 1 hatch, and replacing them with plastic disks to

look more realistic; the rest of the trucks had a square gap filed in the

solid front and rear wheels so they would look more three dimensional.

|

|

|

| Overall view of the finished Liberty ship model from the port side. | Overall view of the finished liberty ship model from the starboard side. | |

|

|

|

| Bow and forward cargo holds, showing the 'Russian' 2-1/2-ton trucks, motor launches, jeeps and other deck cargo. Note the 'repainted' area of the deck under some of the jeeps. | Overall view of the superstructure, with more deck cargo on the No. 3 hatch and the port lifeboats leaning in towards the superstructure because of the roll of the ship. | |

|

|

|

| The superstructure and aft hatches, showing the P-40 fighters as deck cargo, along with some Dodge weapons carriers and still more 'Russian' trucks. It's funny that no matter how carefully I laid them out to get an idea of what fit where, they never fit exactly that same way when the time came to glue them down! | The stern of the Liberty ship, with the cable for the barrage balloon trailing off the winch I mounted there. Note that some of the P-40s have painted on 'canvas covers' over their engines, just to mix things up a little. | |

|

|

|

| Close-up of the forward superstructure, showing the flying bridge, pipe and half track deck cargo and some of the 20mm gun tubs with their asphalt armor. | Close-up of the aft superstructure, and the fighters and vehicles as deck cargo on No. 4 hatch. The yellow squares in the life rafts are the survival packs. Note how the starboard lifeboats are hanging out from the side of the ship due to the heavy roll I induced in the model. |

Here is a fairly complete list of all the added bits:

Gold

Medal Models

Skywave/Pit-Road

Loose

Cannon Productions

Imex Model Co.

One final note about the U.S. Merchant

Marine in WWII - a lot of people at the time characterized these men (and

a few

women) as slackers, draft dodgers, or worse. But when all the

numbers

are added up, the Merchant Marine had a

higher casualty rate than

any branch of the U.S. armed services, including the Marines. In 1942,

at the height of the

Battle of the Atlantic, 4,985 Merchant Marine and

Armed Guard died at sea - a rate of almost 100 men per week. Looking

at it that way, the saying "Freedom is not free" rings very true.

There is a memorial

in New York City that pays homage, in part, to the Merchant Mariners who met

their end in the cold depths of the Atlantic Ocean and have no final resting

place. It is maintained by the American Battle Today there are only two Liberty

ships in their original World War II appearance, the S.S.

Jeremiah O'Brien at San Francisco and the S.S.

John W. Brown at Baltimore. Both are fully operational

and go out on regular cruises into San Francisco and Chesapeake Bays,

respectively. The others are all gone.

Monuments Commission.

Monuments Commission.

(2) The John

Randolph's back was broken by the mine. The aft part sank; the forward part was towed back to

Iceland and used as a floating barracks until 1952, when it broke its tow while

being taken to a shipbreakers, and ran aground at Torrisdale Bay, north Scotland, where

most of it was eventually cut up for scrap.

Addition: This model received a second

place trophy in the All Ships/All Scales category at the 2008 KVSM contest.

ALL TEXT AND PHOTOS © COPYRIGHT 2006-2007 BY THE

AUTHOR

AND RESPECTIVE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS. ALL

RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRODUCTION, RETRIEVAL OR STORAGE BY ANY METHOD FOR ANY

COMMERCIAL PURPOSE IS PROHIBITED IF YOU ARE THAT SCUMBAG LAWYER IN CHARLESTON.

SEND COMMENTS HERE.

Return to the Modeling Index Page

This page was last updated Sept. 3, 2013.