Victory Ship Model - Second

Effort

Building the S.S. LaCrosse Victory

In April 2005 I got to see a real, live Victory

ship, the S.S. American Victory, when Dad and I took a cruise on

her in Tampa Bay, Fl. As soon as I saw her massive gray bulk moored next to

the Tampa Aquarium, I knew in my heart that the model I had just finished

was wrong - not in any huge, glaringly obvious ways, but in a lot of little

ways that made my effort, to me, not complete.

So deciding, I took advantage of the day in more

ways than one - I took a ton of reference photos and crawled over, under,

around and through the American Victory, noting big things like

how many ladders there were on each deck and where they were located, and

little things, like whether the bridge deck had 3-bar or 4-bar railing.

I asked Dad  casual

questions about the two Victory ships he had served on, the LaCrosse

Victory and the Atlantic City Victory, like what kinds of deck

cargo they carried on various Atlantic crossings, did he remember the colors

of the hatch covers, specific paint schemes of the ships, and anything

else I could think of, all under the guise of enjoying the day.

casual

questions about the two Victory ships he had served on, the LaCrosse

Victory and the Atlantic City Victory, like what kinds of deck

cargo they carried on various Atlantic crossings, did he remember the colors

of the hatch covers, specific paint schemes of the ships, and anything

else I could think of, all under the guise of enjoying the day.

By the time the American Victory returned

to the dock that day, I had a clear vision of what I needed to do. First

thing was to order another Victory ship kit from a rather bemused

Dave Angelo at Loose

Cannon Productions. Second was to do research - a LOT of research.

I was going to get it right this time!

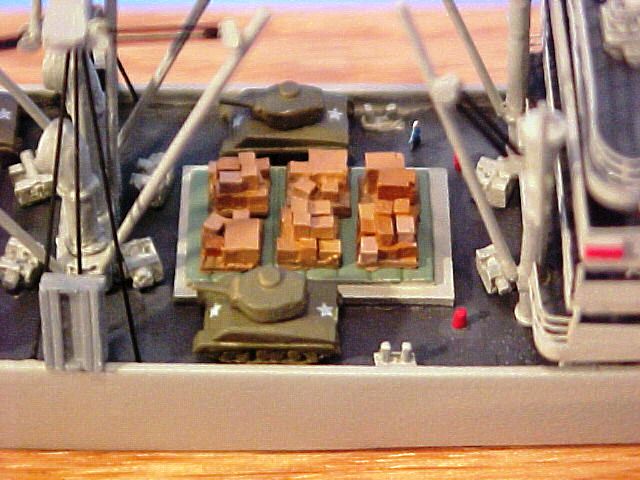

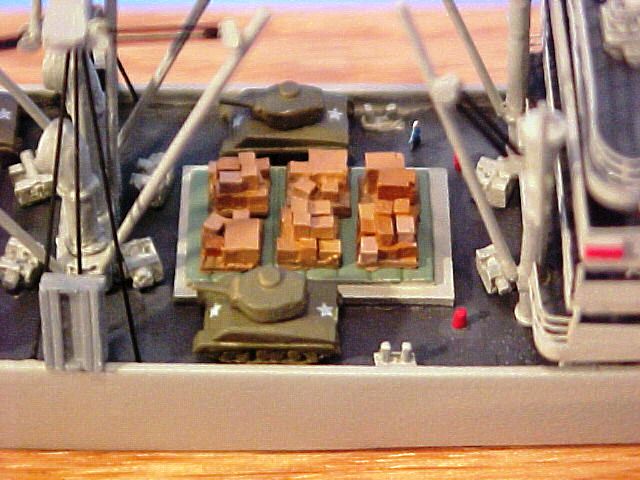

I zeroed in on the LaCrosse Victory for

two main reasons, 1) Dad spent several months on her during the war, and

2) He remembered that one time they carried a deck cargo of tanks over

to Europe. I thought that would look really cool on the finished model.

I also thought it would be really cool to model a specific ship at a specific

moment in time, in this case mid-1945. Plus, the LaCrosse Victory

had a gray paint job, which I thought would be a lot easier to paint than

the black hull and white upperworks scheme of the Atlantic City Victory.

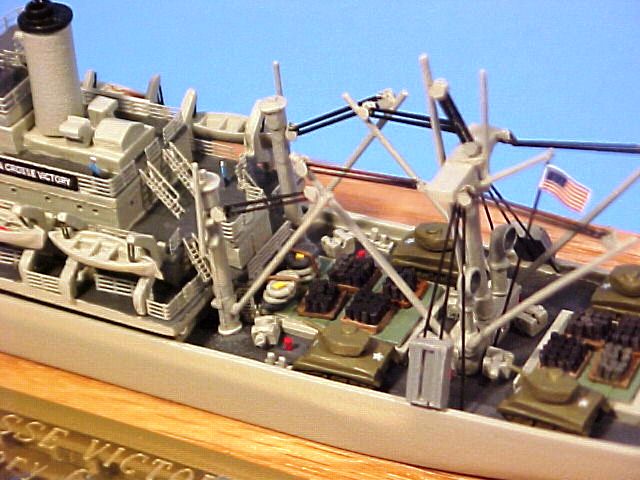

So deciding, I started scouring the Internet for

all the little bits I would need. One thing about 1/700 scale, it defines

tiny. I found one company in England that makes resin tanks, trucks, jeeps,

etc. in that scale and ordered enough to cover the decks. Loose Cannon

Productions came through with resin boxes, crates and fuel drums on pallets.

Other sources in the US and Japan gave me life rings, fire hose racks,

watertight doors, hatch covers, life rafts and a host of other things.

My research efforts uncovered a lot of little

details, like the fact that two of the lifeboats had motors and two did

not. Off went inquiries about who made oars in that scale. The number and

location of the fire hydrants and fire hose racks required calls or e-mails

to the organizations that have the three functioning Victory ships. Where

all the life rings were located was deduced from wartime photos and my time

on the American Victory. By that time of the war the U-boat

submarine threat was almost nil, so the American Victory did not

have any of the 20mm gun tubs or bow cannon so prominent on earlier Victory

ships; based on Dad's recollections, I decided she probably had either

a 4- or 5-inch cannon on the aft

deckhouse. Another search to find out who made the correct kind of cannon

in that scale.

The construction of this model was both faster and slower than my first

effort. Faster because I knew what I was doing, more or less, and slower because

I was adding a lot more detail to this model. If it was on the real Victory

ship, I wanted it to be on this model! A few notes on construction:

PHOTOETCH

Building

model ships in this scale does not require the use of photoetched detail

parts, but it sure makes all the difference between ending up with something

that looks like a pool toy and something that resembles the real thing. A few

things I learned the hard way:

-

Always cut the photoetch on a firm

surface. I use a hard plastic cutting board with a smooth top.

-

Always keep one fingertip, a pencil

eraser, something, on a corner of each part as you make the final cut, or

else you will launch said part into space, never to be seen again.

-

Always use a sharp hobby blade or

razor blade to remove and trim the parts. It may be brass (or steel) and it

may be thin, but it's still pretty tough stuff. I usually use a No. 11 or

No. 12 X-acto blade to remove the parts, and trim the edges flush with a new

single-edge razor blade.

-

It's usually best to paint the

photoetch parts before you remove them from the fret (the framework that

holds them all together) because being so small, it may be impossible to get

at them once they are glued on. If you use spray paint from a can, make sure

you hold it far enough away from the fret so the paint doesn't clog the

details up.

-

Before you paint photoetch, you need

to give it some 'tooth' so the paint will stick. I do this by giving it a

brief bath in ordinary household vinegar, which is acidic enough to mildly

etch the metal, followed by a thorough rinse off in water and air drying.

-

You can use ordinary white glue

(Elmer's) to put

some parts on, provided those parts are never going to be subjected to any

stress - like having a larger part glued to them. Some modelers use white

glue for placement, then come back and flow a thin line of superglue around

the base of the part to make sure it stays put. I tend to superglue items

that require a lot of bending, like railings, since they may try to resume

their original straight shape at some point. Detail parts like hose racks get

put on with a tiny drop of white glue.

-

A piece of fine wire, 24-gauge or so,

makes a dandy superglue applicator. Just trim the tip off when it gets too

big a blob of dried glue on it. You can use this to put tiny dots of

superglue precisely where you want them.

-

My favorite tool for installing detail

parts other than railings is a wooden toothpick. Put glue on the model where

you want the photoetch part to go. Wet the end of the toothpick with your

tongue, touch it to the part to pick it up, and then guide it on in to where

it belongs on the model. The part will stick to the glue and release from

the toothpick, which you can then use to nudge the part into final

alignment.

-

Buy a good set of dividers before you

start installing railings - that is the only practical way to measure

how long a segment needs to be, or how far it is between bends.

-

I bend photoetch railings and other

parts with two single-edge razor blades, one to hold the part down and get a

crisp (straight) bend, the other to slip under the railing or whatever and

bend it up to the required angle.

-

NEVER assume you've bent a railing at

the correct angle before you apply the glue - always check by dry fitting to

make sure that it follows the curves and angles of the deck it's going to be

glued to.

PAINTING

I don't own an airbrush, so I can't get a

lot of those cool effects and crisp details that airbrush users can achieve. I am stuck with spray cans (aka rattle cans) and bottles of enamel

and acrylic paints I get at my local hobby shop. She carries the Testors Model

Masters line of military and naval paints, which fortunately comes in lots

of different shades of gray, green and brown.

Most of my paints are enamels, which means

the brushes have to be cleaned with paint thinner or something similar, and the

rattle cans have to be used outside lest you fill up your abode with poisonous

fumes. I learned pretty fast that anything you spray paint must be

securely nailed down, lest it get blow many feet away by the force of the rattle

can's propellant. I came up with the idea of using small squares of double-sided

foam tape or doubled-over strips of low-tack blue painters tape to secure the

hull to a piece of cardboard that was about an inch larger all around than the

model. That gave me something to hold it with when I spray painted, and to hold

at different angles when I was assembling parts and painting small

details.

The system I came up with was to spray

paint the hull and large superstructure elements after they had been sanded

smooth and any holes or dips filled with modeling putty, check for mistakes and

spray again so everything gets two thin coats. The hull and superstructure of my

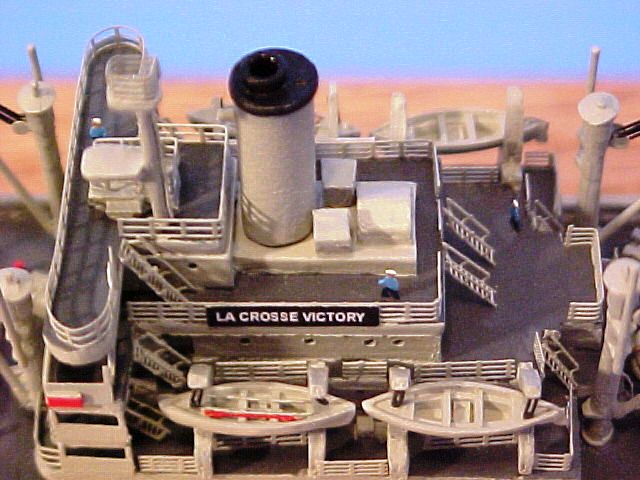

Victory ship were painted Flat Gull Gray (Testors 1930) because merchant ships

in WW II were almost always painted gray, but the exact shade varied from

shipyard to shipyard. All of the photoetch also got sprayed this color.

To avoid the agony of trying to mask off

all the light gray areas, I hand painted the flat deck surfaces with Gunship

Gray (Testors 1723). This darker gray was consistent with the few color photos I

could find, and Dad's memory, plus it gave a nice contrast to the light gray of

the hull and vertical surfaces.

One debate I had with myself was the color

of the hatch covers. The actual covers are large, thick boards, which are then

covered with a piece of canvas that is secured with rope and wooden wedges

around the edges. But what color was the canvas? Dad wasn't sure, but seemed to

think it was just a brown or 'dirty' color of some kind. Talking with a couple of

Liberty and Victory ship historians brought out that, as I suspected, there was

no standard color, just something so that the bright white canvas didn't act as

a beacon for attacking aircraft. General consensus was for some kind of medium

or cream green color. After - again - pondering the dozens of shades of green at

the local hobby shop, I settled on RAF Interior Green (Testors 2062) as looking

the most like new canvas. The LaCrosse Victory was a brand new ship when

my Dad served on her; plus, the cream green color helped break up the large

swatches of gray.

BRUSHES

A few words about brushes - BUY GOOD

ONES.

Because if you buy cheap ones, your models

are going to look like crap. Don't ask me how I know this, just accept it as

fact. If you're building mostly small stuff, as I do, then you'll need

correspondingly small brushes to get the paint where you want it, in the

quantity you want it. Here is my current selection:

-

No. 1, 3, 5, round bristle, for

painting large areas, weathering, drybrushing.

-

No. 0, 2/0, 3/0, round bristle, red

sable hair, for general small area painting.

-

No. 10/0, round bristle, red sable,

for smaller detail work.

-

No. 15/0, round bristle, red sable,

for very small detail work, like one teensie drop of paint on the tip of something.

-

No. 18/0, round bristle, red sable,

called a 'spotter' for obvious reasons.

-

1/4, 3/8, 1/2-inch, flat bristle,

camels hair, for general weathering, applying glue for groundwork, anyplace

I can get away with just globbing on the paint and not having to worry about

the finish.

It takes practice to get a good, smooth

finish using brushes, but it can be done if you pay attention to your stroke

technique, always paint with a wet edge, and keep the paint thin enough to flow

but thick enough to cover with one application. Modeling is a learning

experience, and every project will be better than your last one.

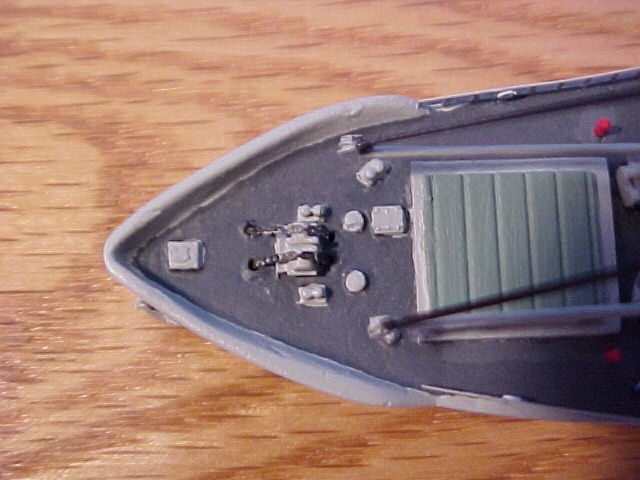

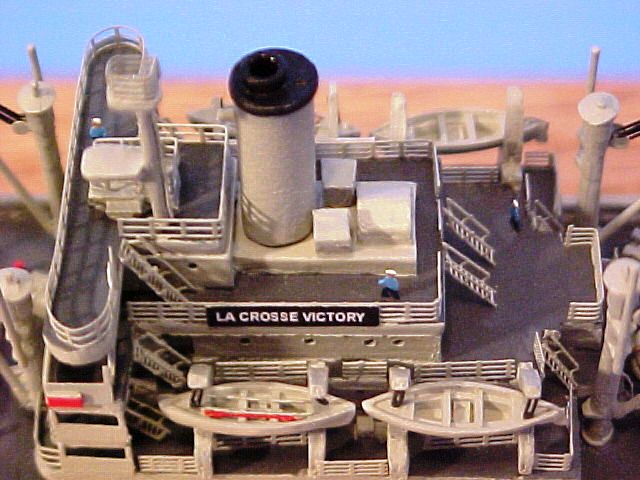

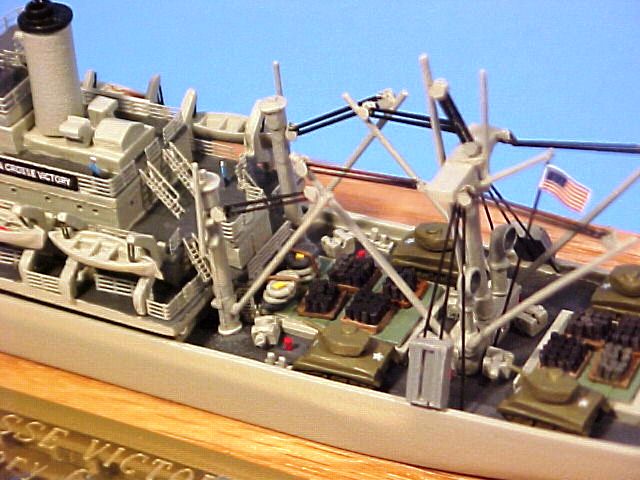

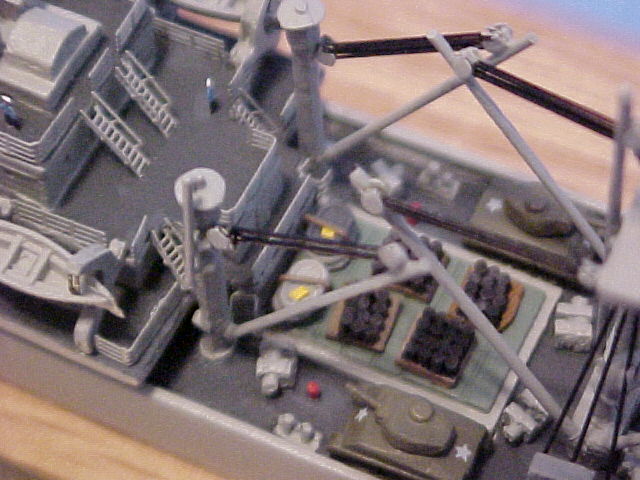

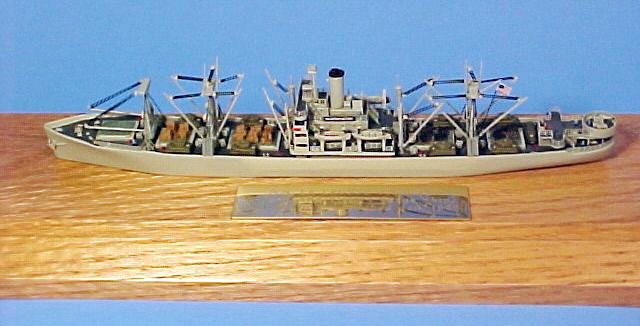

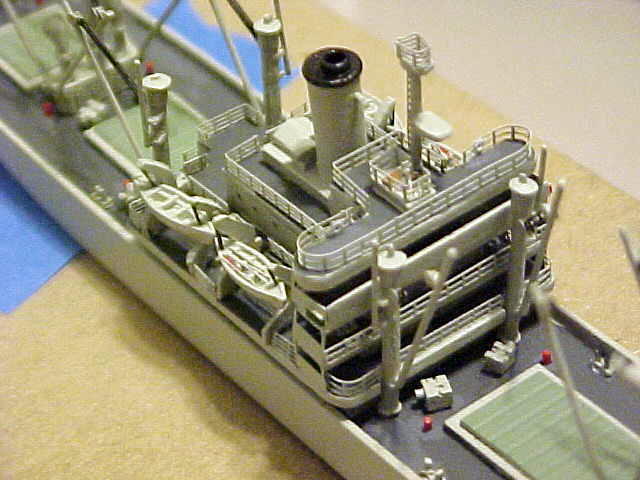

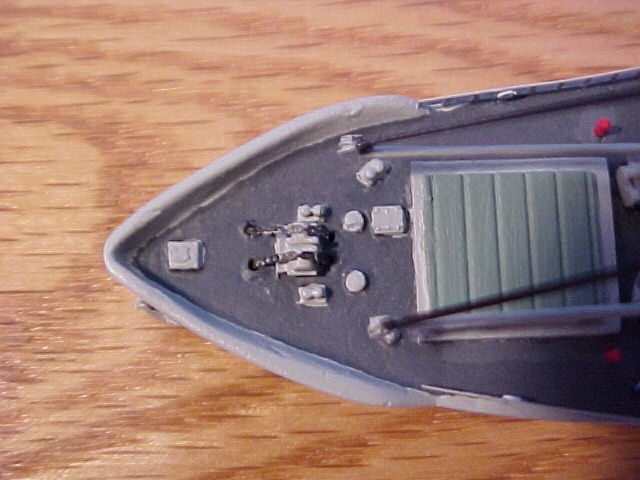

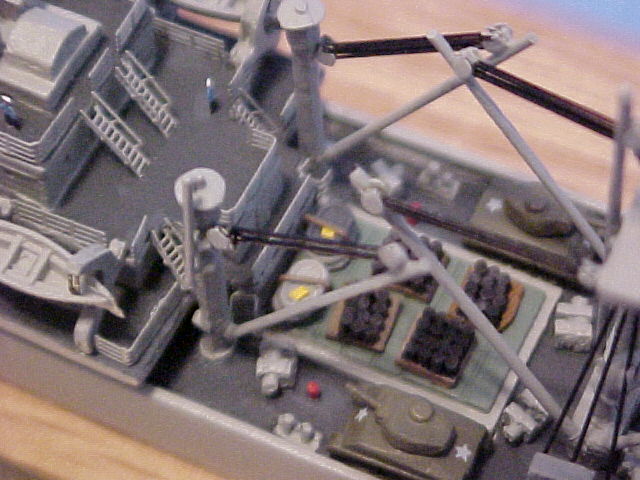

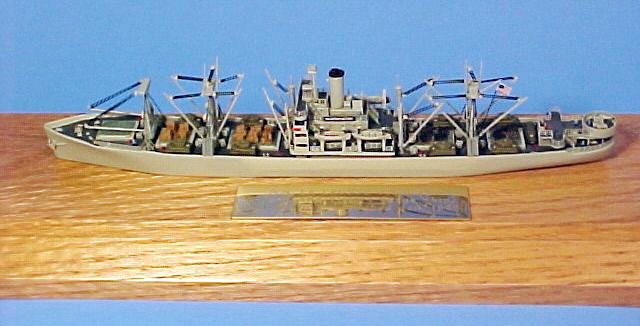

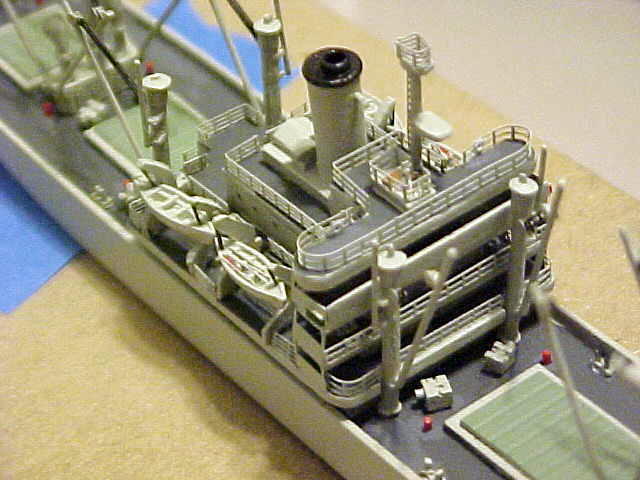

Here are some close-up pictures of the finished model.

Hold cursor over each photo for more information:

The final touch was a brass plaque mounted in

front of the ship on the base. It ended up costing almost as much as the model! It was

engraved:

S. S. LA CROSSE VICTORY

VC2-S-AP2 Victory Ship

Launched: January 1945 Scrapped: 1967

Here is a complete list of additions and modification

to the kit by the time I got done with it:

Loose

Cannon Productions (Kit No. 14, Victory ship)

-

Added portholes on main deck superstructure and aft

deckhouse.

-

Bored out all portholes for depth of field.

-

Added bulwark for aft steering station.

-

Removed 20-mm gun tubs from aft deckhouse.

-

Added fire hydrant stations to main deck.

-

Added deck cargo – pallets of fuel drums, boxes, crates

(purchased separately from LCP).

-

Added nameboards to sides of bridge deck, made from paper

and reverse printed in Microsoft Word.

Gold Medal Models

-

Added photoetched life rings, fire hose racks and

watertight doors to all decks (No. 700-22).

-

Added American flag decal (sheet no. 700/350 1D).

Tom’s Model

Works

-

Added additional photoetched railings and inclined ladders

(all from No. 708).

-

Added photoetched anchor chain.

-

Added photoetched anchors.

-

Added photoetched flying bridge and aft deckhouse

steering stations.

-

Added 10 photoetched seamen and gun crew.

Skywave/Pit Road

-

Added 6 life rafts (kit SW-1000).

-

Substituted open lifeboats, 3-inch deck gun (SW-1000).

-

Added extra anchor at foredeck (SW-1000).

-

Added white star decals for vehicles (kit SW-400).

White

Ensign Models

-

Added 8 Sherman tanks as deck cargo (No. DM-7013).

-

Added 1 White halftrack as deck cargo (No. DM-7043).

-

Added photoetched oars to forward lifeboats and tillers

to aft

lifeboats (No. PE-739).

Evergreen

Scale Models

-

Various sizes styrene rod and strips for minor scratch

building (No. 101, 129, 219).

Today only three Victory ships in their wartime

appearance remain of the 534 that were built. Both the S.S.

Lane Victory, in San Pedro, Calif., and the S.S.

American Victory, in Tampa, Fl., are operational and go out for occasional

day cruises. The S.S. Red Oak Victory

is currently being restored to operational status in Richmond, Calif. All three

are open for tours, at a very reasonable cost.

One final note about the U.S. Merchant

Marine in WWII - a lot of people at the time characterized these men (and

a few

women) as slackers, draft dodgers, or worse. But when all the

numbers

are added up, the Merchant Marine had a

higher casualty rate than

any branch of the U.S. armed services, including the Marines. In 1942,

at the height of the

Battle of the Atlantic, 4,985 Merchant Marine and

Armed Guard died at sea - a rate of almost 100 men per week. Looking

at it that way, the saying "Freedom is not free" rings very true.

There is a memorial

in New York City that pays homage, in part, to the Merchant Mariners who met

their end in the cold depths of the Atlantic Ocean and have no final resting

place; it lists the names of 4,609 missing in the waters of the North Atlantic.

Addition: This model received a

second place medal in

the Ships category at the 2014 KVSM contest.

ALL TEXT AND PHOTOS © COPYRIGHT

2005-2006 BY THE AUTHOR. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRODUCTION, RETRIEVAL OR

STORAGE BY ANY METHOD FOR ANY COMMERCIAL PURPOSE IS PROHIBITED IF YOU ARE THAT SCUMBAG LAWYER IN CHARLESTON. SEND COMMENTS HERE.

Return to the

Modeling Index Page

This page was last updated March

22, 2014.

casual

questions about the two Victory ships he had served on, the LaCrosse

Victory and the Atlantic City Victory, like what kinds of deck

cargo they carried on various Atlantic crossings, did he remember the colors

of the hatch covers, specific paint schemes of the ships, and anything

else I could think of, all under the guise of enjoying the day.

casual

questions about the two Victory ships he had served on, the LaCrosse

Victory and the Atlantic City Victory, like what kinds of deck

cargo they carried on various Atlantic crossings, did he remember the colors

of the hatch covers, specific paint schemes of the ships, and anything

else I could think of, all under the guise of enjoying the day.