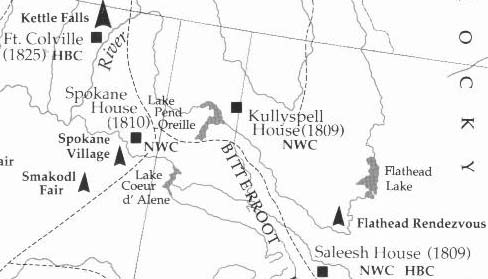

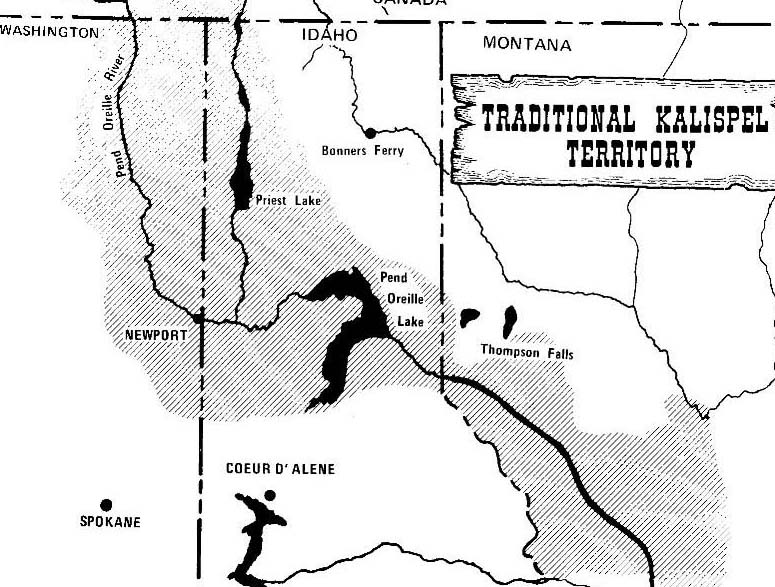

For the Kalispels, one the most wrenching experiences sparked by this encounter was the movement in 1854 of St. Ignatius Mission from its original site in the northeastern part of present-day Washington state to the northwestern part of Montana (Figure 1. shows the locations of these two places).

St. Ignatius Mission in Montana has been designated a National Historic Site. Visitors at this site today read about the beginning of the Mission, "Finally at the request of the Indians themselves, the Mission was transferred to its present location in 1854" (St. Ignatius pamphlet 2) Accounts left by the St. Ignatius missionaries record that the Kalispels "initiated" the move because they were starving to death at the Mission on the Pend Oreille River (Schoenberg's Paths 59). The missionaries also wrote that the Kalispel chief Alexander pointed out and led them to the new site for the Mission (De Smet 299).

The dominant view held by historians is that the Kalispels requested and initiated the tribe's relocation from Washington to Montana and pointed out the new place and led the missionaries there. On the surface, this reasoning seems to be plausible, because many Kalispels were baptized and most of the Kalispels did follow the missionaries to Montana. However, these summary views, perpetuated in tourist literature and promulgated by most historians, do not present the complete story about the relocation of St. Ignatius Mission. In this paper it is argued that the Kalispels did not want to give up their home along the Pend Oreille River and move to Montana.

The St. Ignatius Mission, Montana National Historic Site tourist literature does not state that the Kalispels who did follow the missionaries to Montana were rebuked into doing so or that the Kalispels returned to the Pend Oreille River valley within a year. These facts show the disillusionment of the Indians about the move in stark contrast to the glad narrative that the Indians "requested" and "initiated" the move. The missionaries wanted the Indians to give up there nomadic lifestyle and farm. To establish this farm life the Catholics planted, unknowingly, crops in the Pend Oreille River flood plain. The daily survival problems at St. Ignatius on the Pend Oreille River were caused by the missionaries.

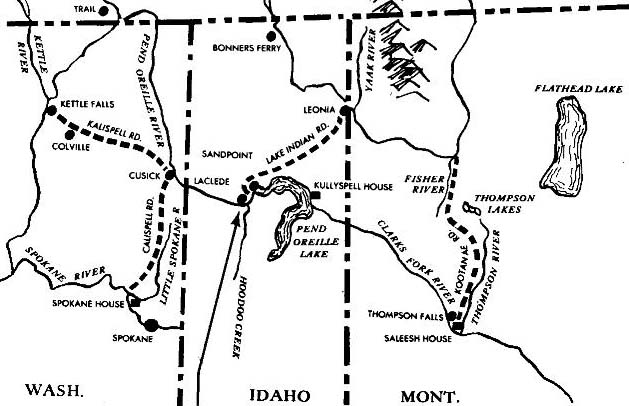

The Montana spot the Kalispel Indians pointed out to and led the missionaries to was known as Snieleman or Sinielman, a word meaning meeting place or rendezvous in the Kalispel's Salish language (St. Ignatius Mission, Montana brochure 5, Schoenberg's Paths 59). Sinielman was considered to be a common ground for all neighboring Indian tribes as illustrated in Figure 2. In this paper, it is asserted that selection of this type of site was at the request of the Missionaries and that the Indians pointed out or led the missionaries to a place that fit the plans of the Catholic missionaries and American government.

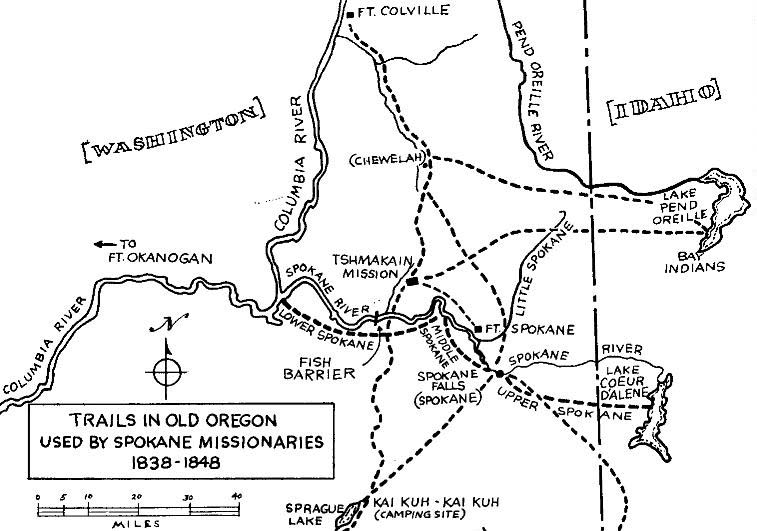

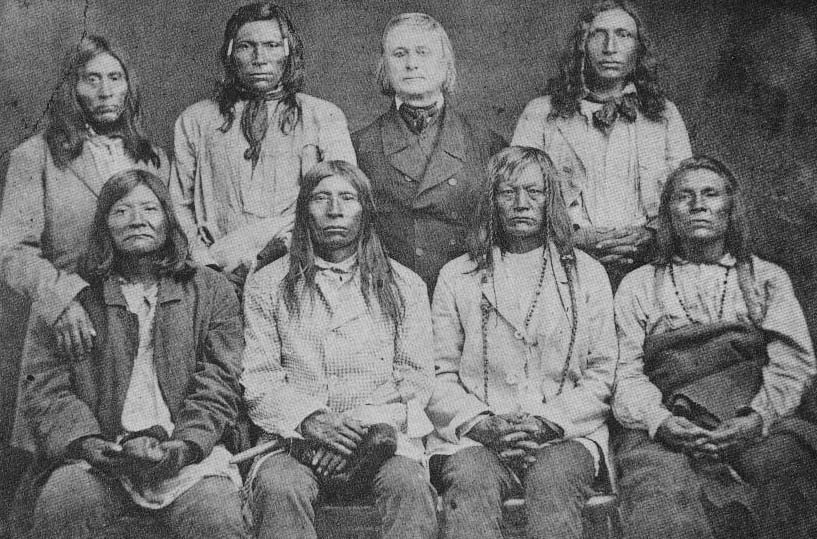

During the ten year life of St. Ignatius Mission, Washington, the Catholic Rocky Mountain mission reduction system, after promising beginnings, was falling apart. In the decade before 1854, missions (see Figure 3. for locations) to the Flathead, Colville, and Blackfeet Indians had been closed (Peterson 24). The Whitman's were massacred in 1847 at their mission at Waiilatpu, Washington causing a stir in Indian and white relationships. The massacre prompted the closure of most all other missions of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in the old Oregon territory, including the Tshimakain Mission to the Spokane Indians (Drury's Nine 433, Drury's Elkanah 207). The Spokanes are neighbors to the Kalispels and live to the southwest as seen in Figure 4. Military awareness had suddenly become a government priority after the Whitman Massacre and the Cayuse War of 1848 (Shoenberg's Path 59). Personal safety was on the minds on the Catholic missionaries and the American government in 1854.

The Washington Territory was created in 1853 and Isaac Ingalls Stevens was appointed the first Governor. Stevens was also in charge of the United States Coast Survey which had the task to survey a railroad route from the Mississippi River to Puget Sound and he was also was the superintendent of Indian affairs in the Washington Territory (Meany 159). In 1853 Dr. George Suckley, army physician to Washington Territory survey party , visited the Kalispel Mission on the Pend Oreille River (Cotes 23). Lieutenant John Mullan was tasked with surveying a road from Fort Benton on the Missouri River to the old Fort Walla Walla on the Columbia River and he also came in contact with the St. Ignatius missionaries (Shoenberg's Path 59). From these contacts, the priests of St. Ignatius were participants in planning the solution to the Indian "problem."

The time period 1844 to 1854, the tenure of St. Ignatius Mission at the Pend Oreille river, saw rapid changes occurring in the old Oregon Territory brought on by increasing white settlement. The remotely-located, isolated Kalispels were quickly surrounded by government and missionary policies that sought to destroy Indian culture and transform them into Catholics and Americans. The decision to move St. Ignatius Mission was prompted by the priests because they wanted to consolidate at a centralized location to better serve the region's Indians on land of the future Flathead Indian Reservation. The Flathead Indian Reservation was established just ten months after the relocation in 1855 (Bergman 31-32). The Kalispels believed in the mystical powers of the missionaries and followed them.

The word kalispel is said to mean "camas root people" and is the Indian name for the tribe which French fur trappers called "Pend d'Oreille" because of their custom of wearing shell ear ornaments (Phillips 20).

The Kalispels' way of life for their food supply was dictated by the seasons and nature's cycles. There were no salmon on the Pend Oreille River because the salmon could not make it over through Z Canyon on the Pend Oreille River, so the Kalispels traveled to the Columbia River via the Kalispel Trail to obtain salmon. The Kalispels would travel to hunt Buffalo in the plains of Montana with their neighboring tribes. The Pend Oreille valley area had an abundance of deer, fish, geese, ducks, and wild berries. Along the Pend Oreille River valley at Usk and Cusick, Washington there was a great Camas growing area covering thousands of acres.

Recent important archeological evidence, the finding of camas processing ovens and sites, shows that the Pend Oreille or Kalispel Valley area has been continuously occupied for well over 3,500 years. This information provides support for the theory that camas and other root foods may have been as important, perhaps more important, than salmon in leading to a more settled life because there were no salmon on the Pend Oreille River (1991 Thoms 52). The facts seem to indicate that the Kalispels were getting along fine hunting, fishing, and gathering food before European encroachment and the founding of St. Ignatius in 1844.

Everyone quested after a guardian spirit personified by some animal, bird, fish, plant, or place. The belief is that because nature is more powerful than men, men need help or medicine. The guardian spirits were found through solitude and fasting on vigils to such places as the sweat lodges by the river, to the wilderness, to mountain tops, or even to graveyards. Words, songs, chants, music (drum and rattle), ritual ceremonies, and objects had supernatural power to heal and protect.

In the Kalispel Indian religion, a great variety of spirits, both good and bad, were believed in. The medicine man was important as a healer, prophet, and protector. Before a hunting trip, it was expected that the shaman would provide powerful hunting spirits and powers to ensure success.

One legend tells of an Indian, Shining Shirt, who was a hero to both the Flathead Salish and the Kalispel. Shining shirt predicted that men with fair skins and long black robes would one day come to teach the truth, to give a new moral law, and to stop the wars with the Blackfeet. After the coming of the Black Robes, other fair skins would arrive and overrun the country and make slaves of his people, but they should not be resisted (Bergman 8-9; Peterson 17). A similar tradition is found with the Spokane and Coeur d'Alene, Kalispel neighbors, Indian prophet Yureerachen or Circling Raven (Ruby and Brown 31-32).

Thus the Kalispels were told that a new trail to heaven was coming from white-skinned people that would also bring the Indian people tears of joy and tears of sorrow. It is seen that the Kalispel religion had much in common with the Catholic religion. When the missionaries came in 1844, the backdrop for prosperity for both the Kalispels and Catholics was promising.

David Thompson worked for the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company in the overland fur trade in what is now Canada and the Pacific Northwest of America. That time was spent trading, establishing new posts, surveying, and checking by astronomical observation over 3,500 miles of wilderness in the interior west of Hudson's Bay (Flandrau 13). Thompson's exploring and charting work was well thought of and he was known as "the astronomer" for his utilization of the stars to fix his location on the earth. He was the first to take serious interest in the religion, philosophy, and culture of the native peoples. The fur trade was extending westward from Hudson's Bay in search of better fur areas and faster water routes to market. Thompson had a desire to see and map the country beyond the present day named Rocky Mountains.

It is this quest that brought him to the present-day Pend Oreille River. Thompson first crossed the northern part of the Rocky Mountains in 1807. He was the first white to see the source of the Columbia River. From the Kootenai Indians, David Thompson knew of a river that emptied into salt water. He also learned of the Columbia River by reading Captain George Vancouver's journals at Grand Portage on Lake Superior.

David Thompson is the first white man known to have visited what is present day Pend Oreille County in northeast Washington State (1932 Elliot 18). Thompson kept journals of these trips that were first published by T.C. Elliot in 1932. He made three journeys down the Pend Oreille River, called Saleesh by Thompson, in 1809, 1810, and 1811 exploring a water route to the Pacific Ocean from the east (1918 Elliot 15). Thompson's journals hint that he was familiar with the area and it can be deduced that he was preceded by others, most probably his clerks Finan McDonald and Jacques Finlay.

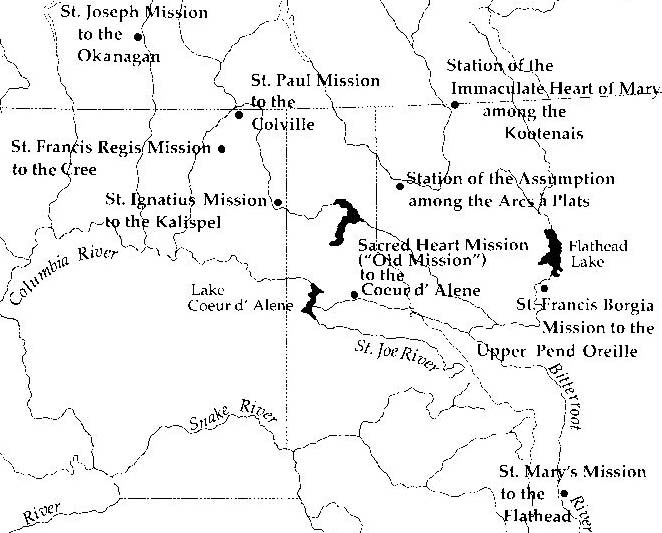

Traveling by way of the Kootenai River, Montana, illustrated in Figure 6., Thompson's group made it to Pend Oreille Lake, Idaho on September 9, 1809 and began building a trading post called Kullyspell House. Kullyspell is the name Thompson said the Indians called themselves. The Kalispel Indians occupied an area along the Pend Oreille and Clark Fork rivers from northeastern Washington to northwestern Montana; refer to Figure 5.

From Thompson's own writings it is learned that between September 26 to October 6, he made a journey of exploration down the Pend Oreille River. During this horseback trip, he met Indians and writes that he asked them how far it was to the Columbia River. The Indians helped make a map to the Columbia and Thompson borrowed a canoe from them. He turned around near present day Cusick, Washington because he had to start a trip back to the east to keep an appointment with James McMillan near present-day Jennings, Montana (1932 Elliot 22). Thompson is the first white known to have traveled down the Pend Oreille River in Idaho and Washington.

David Thompson's second journey down the Pend Oreille River occurred the next spring between April 24 to May 1, 1810. He again began at Kullyspell House and this time made it up the Pend Oreille River to present-day Box Canyon below Ione, Washington. Thompson's diary tells that there they put ashore and climbed high ground to get a view of what was ahead. He learned much information from the Indians about possible land and water routes to the Columbia and due to the described difficulty in the routes Thompson "concluded that we must abandon all thoughts of this way & return ... till future opportunity shall point out some more eligible which I very much doubt" (1932 Elliot 91-92).

The next opportunity to search for the Columbia was a year later during June 7 to June 14, 1811. Following the Kullyspell Indians' advise that the Pend Oreille River did not provide a viable foot or water route, to the Columbia River, a canoe trip was made to get to the Kullyspell Road located near present-day Usk, Washington (1932 Elliot 175). Thompson would take this road to the Spokane House from which he explored the Columbia River to Kettle Falls, Washington (1918 Elliot 13).

The good relations the Hudson's Bay Company enjoyed with Indians was seen in a negative light from the American settlers view. The Americans accused the Hudson's Bay Company of plotting with the Indians to undermine the United States of America settlement progress in instances such as the Whitman massacre, the Chehalis treaty council failure, and the 1850's Indian Wars (Murray 30).

The old Oregon country's abundant natural resources provided a good life at farming, lumber, fishing, and hunting. Growing enthusiasm, during the 1830s and 1840s, for the Oregon Territory compelled Americans to immigrate in search of a better life. The new settlements created conflict over land ownership because there were Indian peoples already living in the Oregon Territory.

The American emigrants wanted to live on land of their choosing with no interference from the natives; the settlers thought that the Indians needed to be tamed and trained to become civilized like whites or would be exterminated. The Hudson's Bay Company and the United States government thought missionaries tended to pacify the Indians, brought peace and order in their wake, and would be assets in time of trouble (Schoenberg's A History 26).

The request by the Indians may possibly be explained by considering the prophetic legends of Shining Shirt and Circling Raven. The Indians were looking for to fulfill this vision. "The explanations also derive from the influence of other Indians, such as Spokan Garry ..." (Peterson 83). Spokane Garry was sent by the Hudson's Bay Company to a mission school at Red River Colony near present-day Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Garry returned to the Spokanes in 1831 with a Bible and knowledge of Christianity and began teaching the other Indians (Ruby and Brown 59). The words of Garry sounded similar to the teachings of the Indian medicine men and prophets. Also, the Indians gained knowledge of Christianity through the fur traders in the area.

It is possible the Indians thought they could become powerful, like the settlers and missionaries, through the white man's books and religion. Most Indians did not write to communicate at this time and probably felt the white man's written, no talking or signing, communication supernatural. Early contact with settlers and missionaries that said religion was the basis of their life, might have made the Indian want to learn about this religion to capture a portion of the white's power.

In the 1830s, the political climate in Europe spurred an increasing anti-clericalism, forcing Catholics to seek relief through missionary work in undeveloped lands. American urban areas were not significantly more hospitable to Roman Catholic presence than certain regions of Europe, so a major portion of the Jesuits who came to America in these years were directed to mission outposts on the frontier (Carriker and Carriker 2.).

The first Roman Catholic missionaries, west of the Rocky Mountains, were Francois Norbet Blanchet and Modeste Demers who arrived at the Fort Vancouver in 1838. Their primary objective was to convert the Indian peoples living in the Pacific Northwest area. The priests' strategy was to get Indian chiefs to be their teaching assistants. The missionaries' message to the natives was more persuasive coming from the chief. Additionally, the scarcity of Roman Catholic priests and the immensity of the Oregon Territory and British Columbia area necessitated the use of assistants.

The Catholics were accepting of the Indian nature. Father Point, one of the first missionaries at St. Mary's Mission in Montana, captured this essence and said that it is better to graft then to fell. The priests did not teach complicated theology or dogma and presented Christianity as a chronicle of historic events. Conversion meant the Indians were to become civilized and give up their ways, such as Buffalo hunting and medicine bags. These objectives fit in exactly with the policy of the American government (Prucha 136).

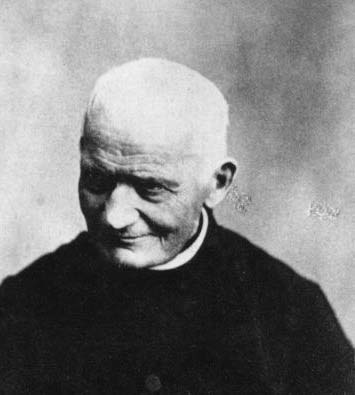

Joset, born in Switzerland, was assigned to the Rocky Mountains Mission in 1843. The historical manuscripts he wrote about the St. Ignatius Mission, Washington were probably written during his tenure as the Superior of the Rocky Mountain Missions from 1846 to 1850 (Joset 675-687).

Joset describes that the Kalispel (spelled Calispel by Joset) life was nomadic. They lived 60 miles below Sandpoint, Idaho (Sandy Point to Joset) on the banks of the Pend Oreille River (called the Clarks' Fork by Joset) eating camas, berries, and game animals. They traveled to the Columbia River during the salmon season because the salmon could not make it past Z Canyon on the Pend Oreille. In the summer, the Kalispel went to Montana to hunt buffalo (Joset 676).

Father Peter DeVos, S.J. and Father Adrian Hoecken, S.J. started the first mission with the Kalispel in 1844 by present day Albeni Falls called St. Michaels (Joset 677). This was the third mission (the others were St. Mary's and Sacred Heart, refer to Figure 3) established in the Rocky Mountain district as part of the planning of Father Peter John De Smet, S.J. De Smet believed the Oregon Country missions should resemble the successful South American system called Reductions. Missions would be located sufficiently distant from white man, convenient to near-by tribes, and self supporting (Carriker and Carriker 5).

De Smet and Hoecken moved the mission four miles down river the next year because of flooding and renamed it St. Ignatius after the founder of the Catholic Jesuit order (Chittenden 473-474). Joset describes the chief of the Kalispels (Standing Grizzly Bear, Christened Loyola by Hoecken) at this time, as "by far the best chief I have ever known" (Joset 678). Joset was pleased that Loyola gave up hunting buffalo to live off the farm and was eager to be instructed by the Jesuits.

Joset describes that the clay soil was not good for growing and that severe winters depleted the surrounding game animals causing the Indians and missionaries to starve. The missionaries asked Loyola to consider moving to land where a good farm could be made. The Kalispels responded saying that God gave them this land and they ought to keep it. Joset relates that the Jesuits then said do not question or complain anymore that you (Kalispel) are starving because of the Catholic Fathers.

After Loyola died, the next chief Victor complains that the missionaries do not love the Kalispels because they are allowing the them to starve to death (De Smet 298). And so in 1854, the Catholics moved St. Ignatius Mission to Montana along with most of the Kalispel Indians. Joset portrays Victor as weak and not standing for order. He writes that the Kalispels continually repeat that they have been abandoned by the black gowns. Joset responds that the Indians have been told to settle in a place where you can live and you will have a priest (Joset 687).

The Kalispels saw Christianity through their own eyes. They wanted the Christian God to strengthen their lives as Indians, not to be like whites. At first, Christianity was added to old beliefs, more medicine.

The two different religious cultures had common ground, both believed: in a mysterious power beyond themselves that made all life possible; that humans, priests and medicine men, could act as intermediaries between the spirit world and this world; that religious experience were searched for in the wilderness and mountains by fasting and aloneness; that words, songs, and objects had powers to heal and protect; in guardian spirits (Jesus and the saints); in rituals like the sacraments that were like medicine and provided a source of healing and life.

The missionaries were immune from diseases that decimated whole Indian tribes. The Indians looked at this as proof that the white's religion was to be listened to and followed. The Jesuits taught that Jesus came back from the dead added to this notion of power.

Dr. George Suckley, an Army surgeon with Washington Governor Stevens' exploring expedition. Suckley's picture lead Stevens to record in an 1855 report to President Pierce that "it would be difficult to find a more beautiful example of successful missionary labors" (Morton 219).

The Indians demonstrated interest in the Christian religion by requesting missionaries, listening willingly, learning quickly, conscientiously performing duties, accepting what the white man wanted and rejecting their own ways, and responding favorably to the Christian message. But in 1855 at St. Ignatius, unhappiness with the white man's religion set in and the conflict between the cultures was evident.

One of the problems was that the Kalispels had no concept of sin, at least not the same idea as the Catholics who wanted the Indians not to go on Buffalo hunts and not to steal horses. The Kalispel resisted the idea of an afterlife, wondering why a loving God would send children to hell and what was the appeal of a heaven with no relatives or buffalo. The Catholics discredited the medicine man as evil and wanted medicine bags burned.

The Indians saw the fundamental antagonism between the Protestant and Catholic missionaries. Both groups said the other group is evil and will burn in hell. The fight between the Protestants and Catholics perplexed the Indians.

The Kalispel were interested in this life not in an afterlife. The Indians were told or made to feel by the missionaries that they were not okay the way they were, that they needed to change to a new religion. The Indians doubted their old medicine and felt ashamed of who they were. Then, sometime in 1854 conversion turned to convergence. The Kalispels realized ever more that the priests were fallible men. The Catholic power did not succeed at St. Ignatius Mission among the Kalispels on the Pend Oreille river.

The Saint (St.) Ignatius Mission and Kalispel people were relocated by the Catholic Jesuits to Montana in 1854. The Kalispels subsequently returned to their land around the Pend Oreille River but the mission no longer existed. The Kalispel Indian tribe was given a reservation in 1914. The heritage of St. Ignatius is that the Kalispels who still live on the reservation are the direct descendants of those Indians who were first Christianized in 1844. The Catholics played an important part in that struggle during St. Ignatius Mission, Washington between 1844 and 1854. The Catholics continue to be a part of the Kalispel life as the Indians are predominantly Catholics.

It is important to know the past to understand the present and create a better future. The sesquicentennial of the founding of St. Ignatius Mission, Washington provides impetus to remember or become aware for the first time of the story of the Catholic mission among Indians in the Pend Oreille River country. The story of the St. Ignatius Mission on the Pend Oreille River provides a look at the most intimate aspect of the contact between Christian missionaries and the Kalispel Indians. The study of the St. Ignatius Mission, Washington 1844 to 1854, provides a view that the struggle between the Natives of the Oregon Territory and the emigrants was difficult for the Kalispel Indians. The Kalispels, and other Native Americans, continue to play a part of the fundamental question whether Indian tribes will vanish by assimilation into American society or remain legally and culturally apart (Fahey xii).

The view that the Catholic Kalispel Mission moved to Montana in 1854 at the request and initiative of the Indians themselves needs to be discarded. The Catholics' prescription to civilize the Indian led to starvation. Also, the notion that the Kalispels selected the new Mission site should always be put in context that the Indians pointed out a site that fit the plans of the Catholic missionaries and the American government. The arrival of Catholic and Protestant, American settlement and government intervention was injurious to the Kalispels' determination of their way of life.

Bond, Rowland. The Original Northwester David Thompson and the Native Tribes of North America. Nine Mile Falls: Spokane House Enterprises, 1970.

Carriker, Robert C. and Eleanor R. Carriker. Guide to the Microfilm Edition of the Pacific Northwest Tribes Missions Collection of the Oregon Province Archives of the Society of Jesus. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, 1987.

Chance, David. H. People of the Falls. Colville, Washington: Don's Printery, 1986.

Chittenden, Hiram Martin and Alfred Talbot Richardson. Life, Letters and Travels of Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J.: 1801-1873. New York: Francis P. Harper, 1905.

Cotes, O.J., ed. The Kalispels: People of the Pend Oreille. Spokane: Kalispel Tribe, 1980.

De Smet, Pierre Jean. Western Missions and Missionaries: A Series of Letters. Shannon, Ireland: Irish U P, 1972 (reprint of 1863 edition).

Drury, Clifford Merrill. Elkanah and Mary Walker: Pioneers Among the Spokanes. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton, 1940.

Drury, Clifford Merrill. Nine Years With the Spokane Indians: The Diary, 1838-1848, of Elkanah Walker. Glendale, California: Arthur H. Clark, 1976.

Elliot, T.C. "David Thompson's Journeys in the Pend Oreille Country." The Washington Historical Quarterly. Seattle: The Washington State Historical Society, 1918.

Elliot, T.C. "David Thompson's Journeys in the Pend Oreille Country."

The Washington Historical Quarterly. Seattle: The Washington State Historical

Society, 1932.

Fahey, John. The Kalispel Indians. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1986.

Flandrau, Grace. Koo-koo-sint: The Star Man: A Chronicle of David Thompson. Great Northern Railway, undated.

Joset, Joseph. "Origin of St. Ignatius Mission." History Manuscripts on St. Ignatius Mission on the Pend Oreille River. (Undated). Microfilm Edition of the Pacific Northwest Tribes Missions Collection of the Oregon Province Archives of the Society of Jesus. 1987.

Meany, Edmond S. History of the State of Washington. New York: Macmillan, 1909.

Microfilm Edition of the Pacific Northwest Tribes Missions Collection of the Oregon Province Archives of the Society of Jesus. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1987. University of Washington Suzallo Library Microforms and Newspaper Section.

Morton, Edmund W. "Historic Mission 100 Years Old." The Spokesman-Review (25 June 1944). Microfilm Edition of the Pacific Northwest Tribes Missions Collection of the Oregon Province Archives of the Society of Jesus, 1987.

Murray, Keith A. "The Role of the Hudson's Bay Company in Pacific Northwest History." Pacific Northwest Quarterly. Seattle: The Washington State Historical Society, 1961.

Peterson, Jacqueline. Sacred Encounters: Father De Smet and the Indians of the Rocky Mountain West. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1993.

Phillips, James W. Washington State Place Names. Seattle: U of Washington P, 1971.

Prucha, Francis Paul. "Two Roads to Conversion: Protestant and Catholic Missionaries in the Pacific Northwest." Pacific Northwest Quarterly. Seattle: The Washington State Historical Society, 1988.

Ruby, Robert H. and John A. Brown. The Spokane Indians: Children of the Sun. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1970.

Schoenberg, Wilfred P. Paths to the Northwest: A Jesuit History of the Oregon Province. Chicago, Illinois: Loyola University Press, 1982.

Schoenberg, Wilfred P. A History of the Catholic Church in the Pacific Northwest, 1743-1983. Washington, D.C.: The Pastoral Press, 1987.

Schwantes, Carlos A. The Pacific Northwest, An Interpretive History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989.

Smith, Allan H. "A Glimpse of Old-Time Kalispel Life." The Big Smoke. Chicago, Illinois: Pflum, 1988.

St. Ignatius Mission: National Historic Site. pamphlet, undated.

St. Ignatius Mission: St. Ignatius, Montana: Historical Guide Book and Key to Frescoes. brochure, undated.

Thoms, Alson V. "The Roots of Village Life." The Big Smoke. Priest River, Idaho: The Priest River Times, 1990.

Thoms, Alson V. "The Roots of Prehistory in the Calispel Valley." The Big Smoke. Chicago, Illinois: Pflum, 1987.