Here's a list of events not too far away for WBA pilots to attend:

5/15 Paine Field (KPAE) General Aviation Day including flights of warbird aircraft from Paul Allen's Heritage Flight

Museum and John Sessions' Historic Flight Foundation (and whose B-25 made a low pass here at KAWO today)

6/11-13 Marysville, CA

6/19-20 Olympia, WA (KOLM)

7/7-11 Arlington, WA Fly-In

7/24-25 Fairchild AFB Skyfest (Spokane, WA)

7/26-8/1 EAA Airventure (KOSH)

8/6-8 Seattle Seafair

8/13-15 Abbotsford, BC, Canada

8/20-22 Hillsboro, OR (KHBO)

8/21-22 Chilliwack, BC, Canada

9/3-5 Watsonville, CA

10/21-23 Copperstate Casa Grande, AZ

14 CFR Part 43 is the section of the FAR's that describes what sorts of aircraft maintenance are required, who can

do what, what approvals are required etc. Paragraph (c) of Appendix A lists all the items that are considered "preventive

maintenance," so long as they don't involve "complex assembly operations," and that can be performed by the aircraft owner,

provided the owner meets several requirements and has the proper documentation to do the job properly etc. The FAA says

one of the top causes of aircraft accidents is maintenance incorrectly performed by aircraft owners. Sorry to say, but

sometimes A&P's screw up, too.

To wit:

Late Saturday evening the pilot of a Pitts S-1T (a type-certificated, production model of the famous Pitts Special aerobatic

airplane) dropped in for some emergency brake repair. The right brake had failed while taxiing following landing

and was puking hydraulic fluid. Note that, contrary to popular opinion, brake repair, other than replenishing hydraulic

reservoirs, is not on the list of things considered "preventive maintenance" by the FAA. Now, I don't know who had last

worked on this aircraft's brakes, but I can say that whoever did the work re-assembled them incorrectly (see pictures below).

They are Cleveland hydraulic disk brakes, common to many models of both certificated and experimental aircraft, simple in

design and easy to work on, but repair is NOT considered preventive maintenance.

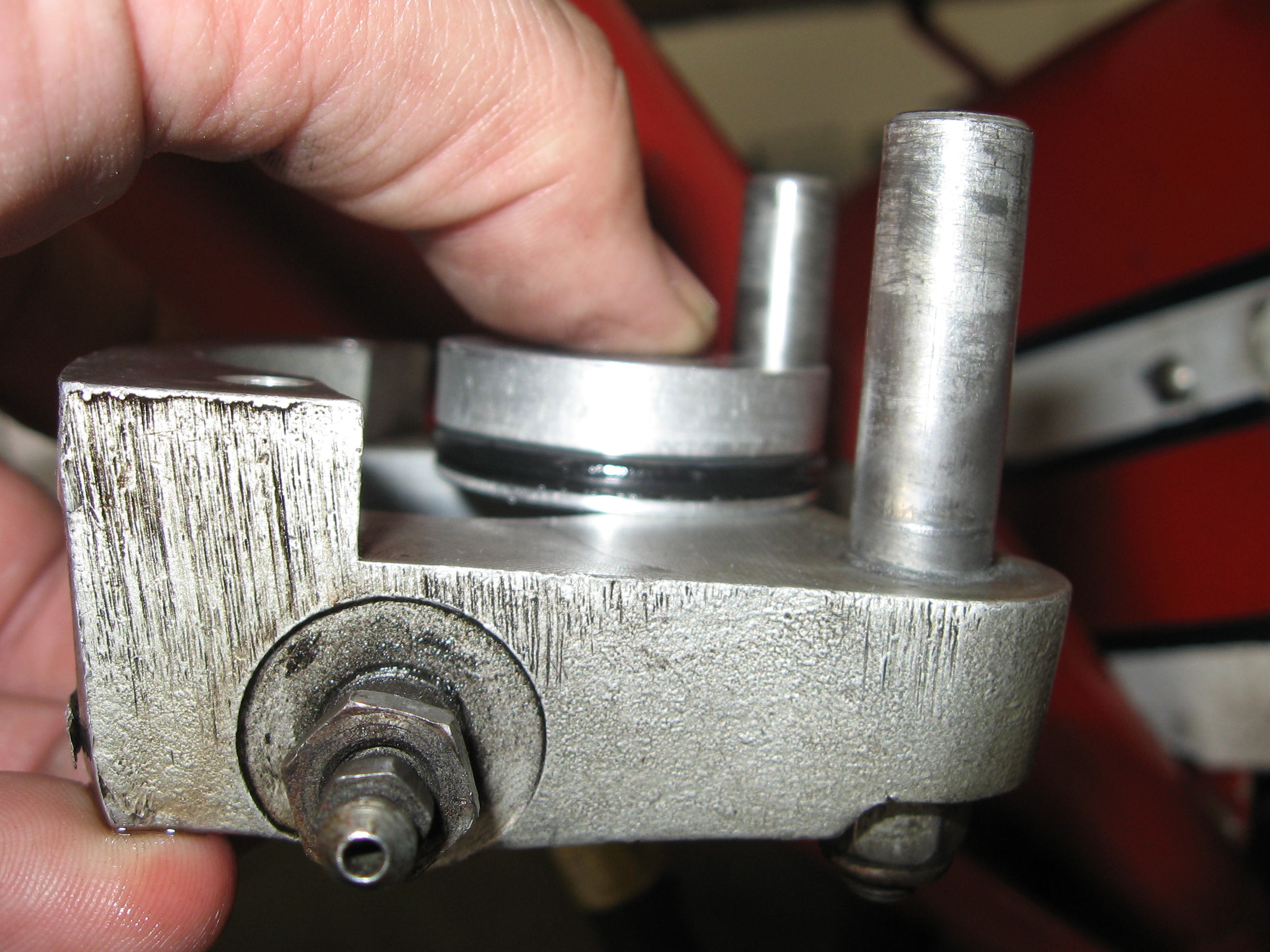

The piston in the brake caliper (just like the piston in an aircraft cylinder) moves back and forth in reponse to

hydraulic fluid pressure on the caliper side of the piston. There is an "O" ring to seal the fluid within the caliper

cylinder. The "O" ring fits in a groove machined into the piston, which is offset to the side of the piston.

The "O" ring, which functions just like the rings on an engine piston, is intended to be on the "pressure" side

of the piston, providing better sealing and, not incidentally, allowing the piston quite a bit of movement within the cylinder

without allowing the "O" ring to escape the cylinder, allowing hydraulic fluid to bleed by the "O" ring.

The picture above shows the brake piston next to the caliper cylinder bore. It should go into the caliper cylinder

as shown, with the "O" ring on the "inside," or pressure side of the caliper, away from the brake disk. You can

see that the piston isn't very thick and that if installed backwards wouldn't have to move very far before the "O" ring would

escape the cylinder bore and allow fluid to escape. The upper side of the piston (in this picture) is adjacent to the

brake backing plate which has friction material riveted to it which rubs against the brake disk. The brake caliper and "shoe"

(or "pad," backing plate and friction material) ride back and forth on the pins you can see in the picture to squeeze the

brake disk, causing friction and braking action. This picture is of the "floating" or "moving" side of the brake.

The brake pad on the other side of the disk (not shown) is bolted to the caliper flange on the upper left. The

whole caliper moves a small amount on the pins to squeeze the disk and accomodate friction material wear.

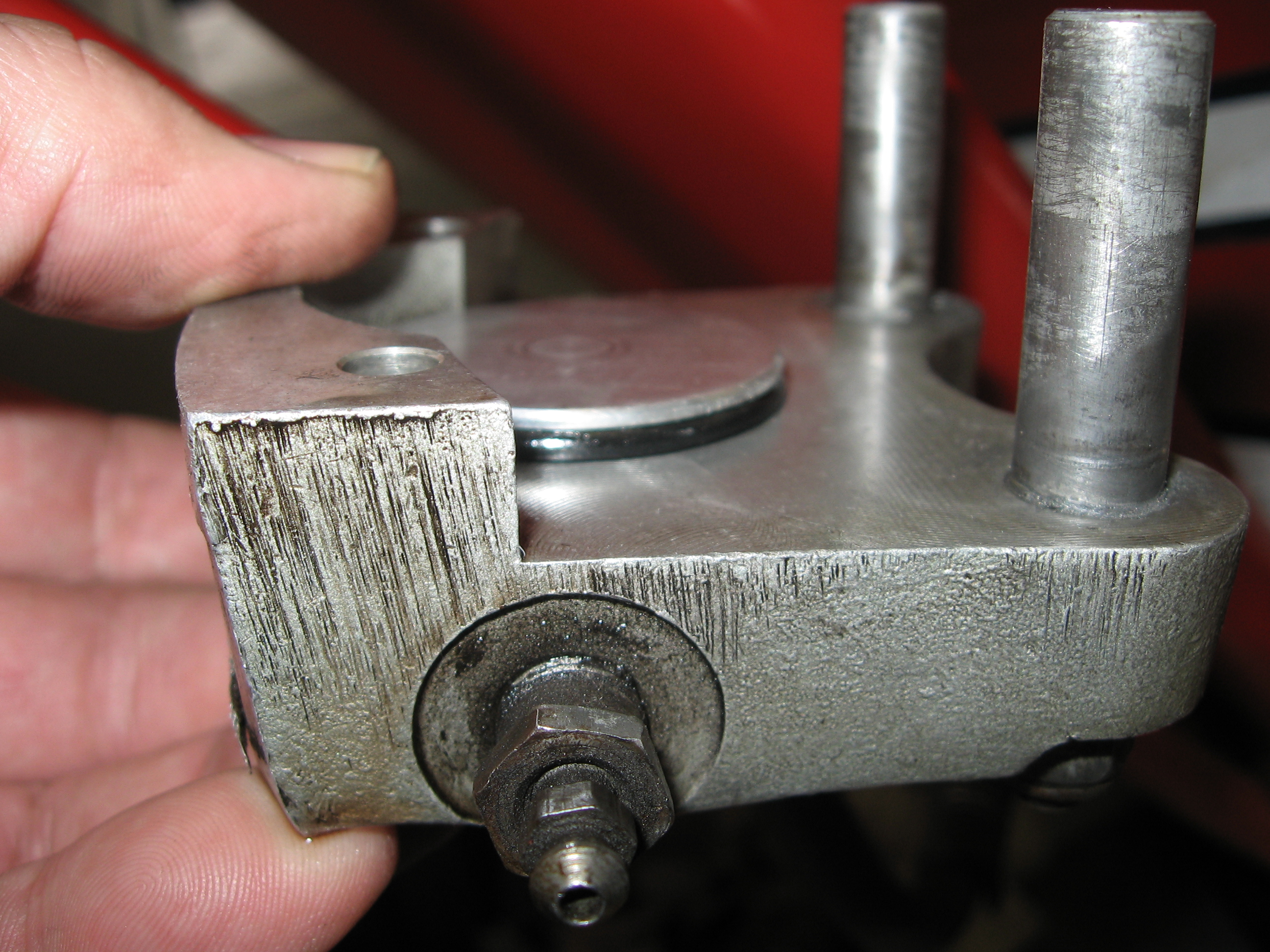

The next picture (above) shows what we found when we disassembled the calipers (both wheels). The pistons of both

brakes had been installed backwards so that the "O" rings were on the disk side of the caliper (not the pressure side).

That meant that only a small movement of the piston would allow the "O" ring to escape the caliper cylinder and allow hydraulic

fluid to pass. Not good, especially in an aircraft like a Pitts, that is short-coupled, lands fast and seems to have

a built-in swerve on both takeof and landing roll.

Fortunately, the pilot didn't suffer brake failure until he was taxiing after landing. If the brakes had failed

on either takeoff or landing the results could have been disastrous.

So, all you owners who are tempted to perform maintenance, whether it is or isn't on the list of "preventive" measures,

and you A&P's, too, make sure you know what you're doing, have the required documentation that shows you how to do it

and are properly supervised when required.